Peter Warburton – September 29, 2021

Two years ago, there was no little consternation over the burgeoning pile of risky corporate loans and structured finance products accumulating in the US and Europe. The IMF, members of the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of Australia all raised red flags over-leveraged loans – covenant-lite loans typically offered to companies already deep in debt. Yet, over the past few months, investors have been falling over themselves to snap up even the riskiest corporate loans and debt instruments. It is hard to imagine that the pandemic has improved the underlying credit outlook for these indebted companies, notwithstanding the welcome but temporary boost from government largesse. When did subprime become sublime?

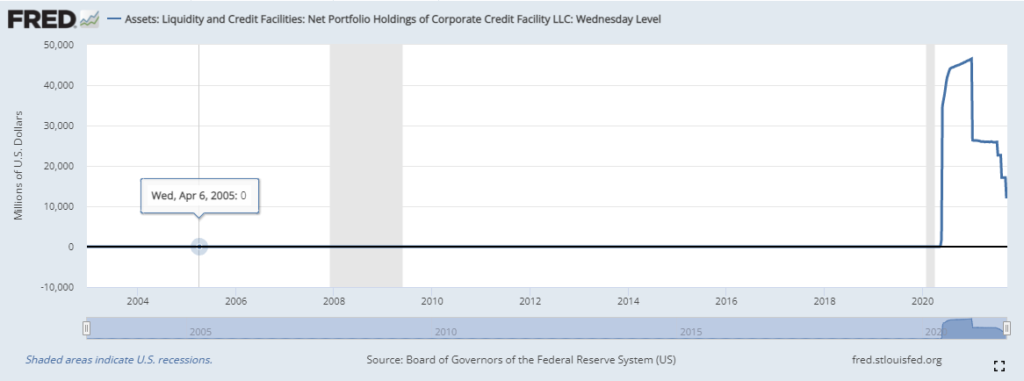

The interventions of the US Treasury and US Federal Reserve in corporate debt markets from March 2020 onwards marked another staging post in the progressive sedation of financial markets. The Fed anticipated, correctly, that should a significant widening in credit spreads occur, this would be associated with worsening outcomes for output, employment and investment over a 2-year horizon. Its actions to forestall this development, long forgotten by market commentators, are no less significant today. In an echo of Mario Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech of 2012, the Fed’s commitment to act in both primary and secondary corporate debt markets was sufficient to stem investor outflows. Figure 1 confirms that little money (US$114bn at its peak, now down to US$40bn) needed to be spent in making good this commitment, but the reassurances were priceless.

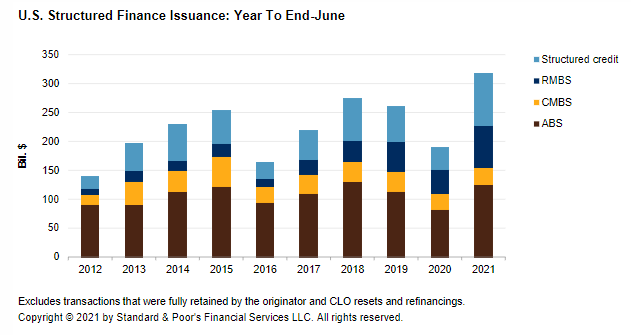

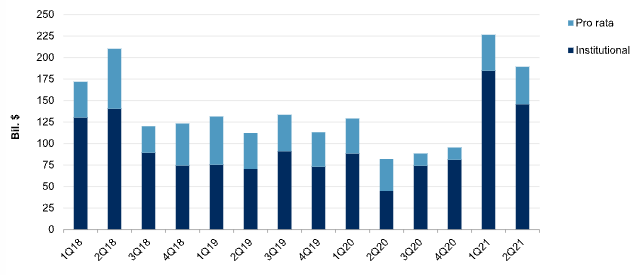

The legacy of this outrageous intervention is the emboldenment of financial risk-taking that allows troubled borrowers to prospect freely for additional funds in the public markets and persuades investors that default scenarios are fanciful and remote, despite the structural damage wreaked by protracted lockdowns. After subdued issuance in 2020, US leveraged loan volumes have surged to new records – over US$400bn in the first half of 2021 (figure 2), and structured finance issuance (ABS, CMBS, RMBS and structured credit) jumped to US$320bn in the year to June 2021 (figure 3). European leveraged loan volumes doubled to €80bn in the same period.

The covenants that were previously deemed essential for the lender’s protection have been airbrushed out, making defaults increasingly rare. According to S&P, the trailing 12-month default rate for junk bonds, now 3.1%, is likely to drop to 2.5% by June 2022. Grant’s Interest Rate Observer (17th September) notes that the 1-year average default rate for each bond, rating by rating, would predict a blended rate of 6.5% by mid-22. The best high yield maturity basket this year is the longest; the best-performing rating category is the worst.

There is no way back from this moral hazard abyss, other than a reality check. If price discovery in the credit markets has been shut down, then the only remaining harbingers of financial sanity are a dramatic event, such as the revelation of a financial scandal or fraud, or the normalisation of credit and monetary policy. This week, the Fed has telegraphed the beginning of tapering at the November meeting. Let’s see if they follow through with it.

U.S Leveraged Loan Volume

Standard & Poor’s Financial Service LLC. All rights reserved.

©