The Russian bombardment is, first and foremost, a tragedy for the population of Ukraine. But a significant secondary consideration is its adverse consequence for global food supply, and the likely increase in death from starvation in other parts of the world. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of wheat and Ukraine the fifth largest. If president Putin has his way, Ukraine will very soon lose its capacity to export crops. Add in the sharp increase in the cost of fertilisers and fuels, that are major inputs to modern agriculture, the lasting damage to global food supply chains from the pandemic and the potential consequences for food prices are obvious. The global economy is being pounded by a series of negative supply shocks: after the energy price shock comes the food price shock.

According to data published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), real commodity food prices (figure 1) have risen to match the record high in 1974. In nominal terms, the price index has also set a record in February 2022, beating the 2010 peak. Commodity food prices take months to influence the food component of the consumer price index, especially in countries where processed foods predominate. CPI data for food and non-alcoholic beverages across OECD countries shows an increase in inflation from 3.5 per cent in August 2021 to 7.5 per cent in January 2022. Turkey (55 per cent), Argentina (50 per cent), and Colombia (20 per cent) lead the table, but food inflation readings in Russia (13 per cent), Lithuania (15 per cent) and Estonia and Latvia (12 per cent) suggest that supply pressures in eastern Europe were already stretched before the invasion of Ukraine.

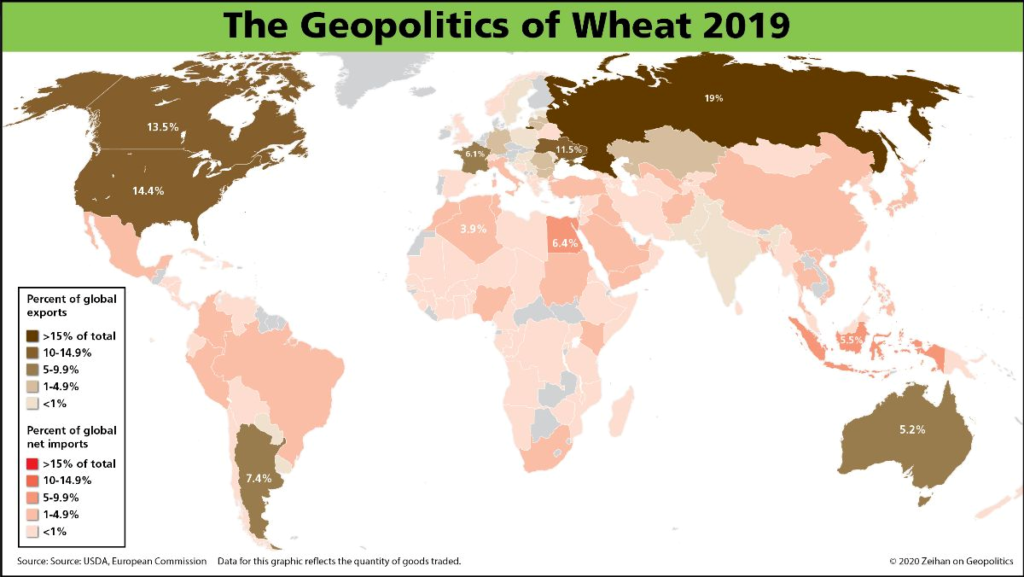

Geopolitics author Peter Zeihan sums up the devastating impact on Ukraine’s agriculture of the Russian onslaught: “… lost in the burning of Ukraine’s large population centres is Russia’s far more methodical annihilation of Ukraine’s towns and villages. The towns and villages that are the bone and sinew supporting the Ukrainian agricultural sector. Ukraine will not plant crops this spring or summer. The world has lost one of its largest and most reliable sources of wheat (figure 2), sunflower, safflower and barley. Nor will Ukraine return to the ranks of major food suppliers anytime soon. Russia’s wave of deliberate destruction will soon reach the port city of Odesa. Not only is Odesa Ukraine’s commercial capital, not only will its fall signal an end to Ukraine’s maritime frontage, but Odesa is also the export point for nearly all of Ukraine’s agricultural bounty. Until it is freed from Russian control and rebuilt, large-scale Ukrainian exports will remain beyond reach”.

Beyond Ukraine, Zeihan argues that we have been “babystepping” to a collapse of agricultural supply chains for over a decade. “In 2022, we will experience breakdowns in the supply systems that make industrialised agriculture impossible, and not just in Africa. The Middle East and East Asia also face a catastrophic unwinding of the input streams that keep regional populations alive, while major agricultural producers like Australia and Brazil will face challenges far beyond their system tolerances. The result is the same in all of them: lower yields. And lower yields mean famine.” The structural damage to supply chains from the pandemic does not begin and end with semiconductors. Fixing global food supply chains when countries are increasingly worried about domestic food security will take considerable time, effort and goodwill. Inflation is here to stay.

Figure 1

Figure 2