The air is thick with threats from members of the Federal Open Market Committee and regional Fed presidents of interest rate hikes and balance sheet shrinkage. Talk of a 50 basis point target funds rate increase in May is now commonplace. Last week’s labour market report painted a picture of employers in a frenetic bidding war for scarce workers. Esther George and Lael Brainard responded in hawkish tones that sent 10-year Treasury yields surging to 2.6 per cent. The fervour of Powell’s Fed, in comparison to the ambivalence of the ECB and Bank of England and the bemusement of the Bank of Japan, has helped to propel the US Dollar to within touching distance of a 20-year high. What could possibly go wrong?

Arguably, there are three things that not only could go wrong but have already done so: the inflation outlook, the normalisation of the US fiscal stance after extreme Covid-related interventions and the escalation of the war in Ukraine. The consensus view – that the US economy will ride out these storms to record respectable growth and very low unemployment – flies in the face of reason and experience. Rather than proposing an appropriate and timely action plan, the US Fed is preparing the ground for another volte face. David Marsh, chairman of OMFIF, goes so far as to suggest that central banks will be applauded for their yet-to-be-announced policy reversals.

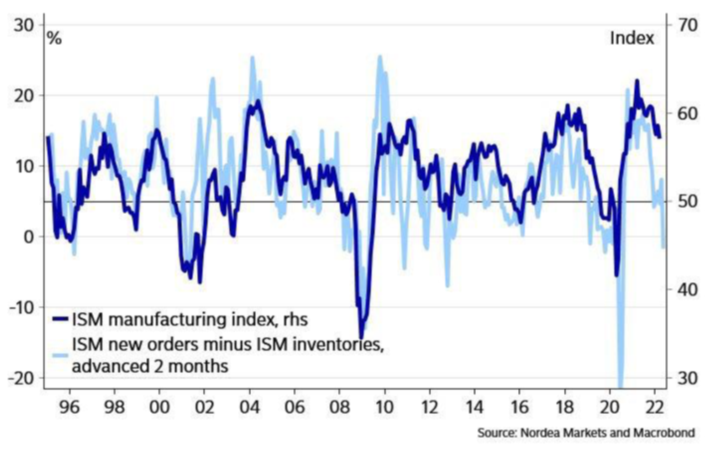

First, the inflation outlook has become more complicated by the direct and indirect impacts of the Russian invasion on energy and grain supply and pricing. Currently 7.9 per cent, US CPI inflation could approach 10 per cent by the summer. Wage acceleration has failed to match the pace of ascent of consumer prices, despite the tightening of the labour market. Consumer spending is being supported by a drop in the saving ratio at present, but that dynamic may well have been reversed by the alarming images of devastation coming out of Ukraine. The Michigan consumer sentiment measure dropped to 59.4 in March, from 67.2 in January. And now the Fed‘s threats have shifted market pricing of borrowing rates more abruptly than since the 1990s (figure 1).

Second, the temporary US fiscal concessions are on their way out. The child tax credit drops back down to $2000 per child in the 2022 tax year, down from $3600 for children under 6 years and $3000 for children aged 6-17. The more generous terms of the child and dependent care credit and the earned income tax credit are being withdrawn also. There will be no stimulus check payments in 2022. On the face of it, the adjustment to the fiscal stance this year is the most severe peacetime contraction ever.

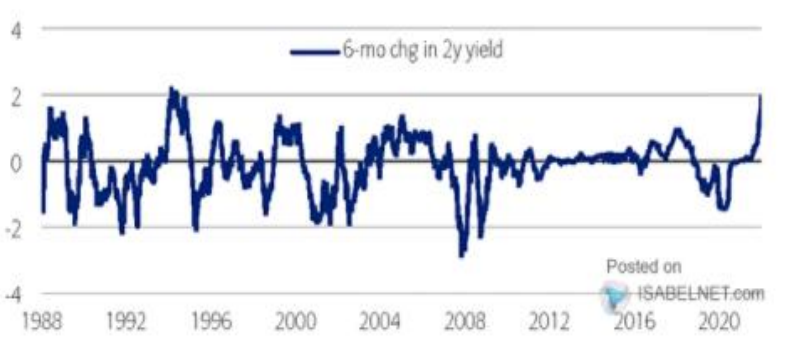

Third, the war in Ukraine might seem a long way away for North Americans, but US citizens should be under no illusion that arming the Ukrainian resistance forces and imposing stringent economic and financial sanctions on Russia could draw retaliatory action that damages US interests. The graphic images of war on our screens are likely to sap consumer and business confidence and cause spending decisions to be deferred (figure 2). So much as happened in the past 6 weeks, that it is much too soon to evaluate the broader economic impact of the Russian invasion.

The Fed’s belated crusade against the surge in inflation has arrived as the administration’s historic fiscal land grab is already underway, as energy and food inflation are soaring faster than wages and as our collective sense of wellbeing and security are challenged again by the horrors of European war. The Fed is a paper tiger, whose threats are likely to become less and less credible as the year wears on.

Figure 1: Market re-pricing of the Fed’s tightening path (6-month change)

Source: BofA Global Research, Bloomberg

Figure 2: Implied forecast for US manufacturing ISM based on April data