The market and media obsession with the Fed’s deliberations on interest rates is obscuring a material threat to US and global financial stability, with serious consequences also for the economic outlook. Three forces are sucking liquidity out of the banking system simultaneously: the depletion of household savings as earnings are eroded by inflation; the lure of better-paying money market funds and the gradual liquidation of the Fed’s bond portfolio. The government is outbidding the banks for funds and risks a severe tightening in monetary conditions for the private sector.

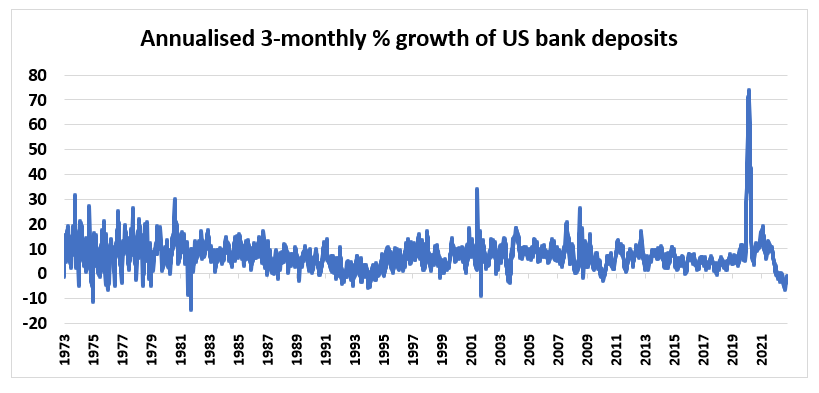

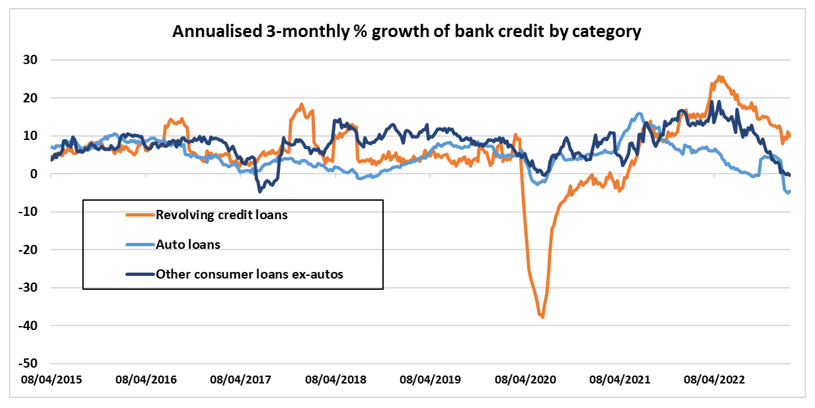

Despite the extraordinary monetary splurge of 2020-21, the consideration of quantities – such as the balance sheet footings of a bank, a non-bank financial institution or the financial sector as a whole – remains out of favour in modern macroeconomics. For those who persist in the belief that a violent monetary expansion had nothing to do with the highest inflation readings in 40 years, it is logical that they attach no significance to the money and credit crunch (figures 1 and 2) that is underway. The rest of us are worried that a highly politicised Fed, still fighting for its credibility, will press ahead with the shrinkage of its own balance sheet and the associated withdrawal of private sector liquidity, blithely unaware of the implied financial stability risks.

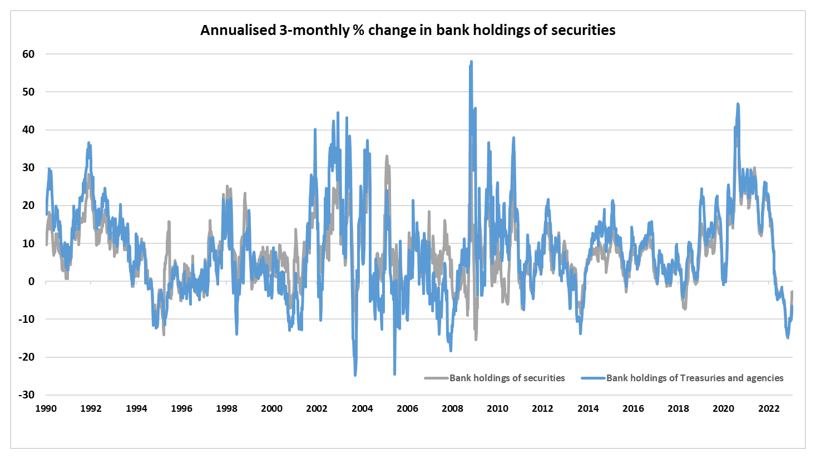

As short-term interest rates rise, so the rate offered by money market funds, which are 80 per cent invested in government paper, also rise. Bank deposit rates have lagged well behind as a deliberate tactic of margin expansion and as a buffer for future loan losses and provisions. As funds migrate to the MMFs, so banks need to sell something. As figure 3 shows, they have been selling US Treasuries and agencies, thus compounding the effect of central bank sales. None of this is good news for bond markets, as we await the inevitable raising of the federal debt ceiling and the pent-up issuance that will follow.

As an aide memoire for the equity market, the previous episode of QT lasted 2 years, beginning in July 2017, and the annual pace of balance sheet reduction was 8 per cent. The decision to phase out QT was taken at the back end of 2018, after the S&P 500 slumped by 17.5 per cent in 3 months. The current QT experiment started with a Fed balance sheet almost exactly twice the size that it was in July 2017 and has again proceeded at around an 8 per cent annual pace. The prospect of a sudden tightening of financial market liquidity that punctures asset prices is eminently plausible after January’s silly rally.

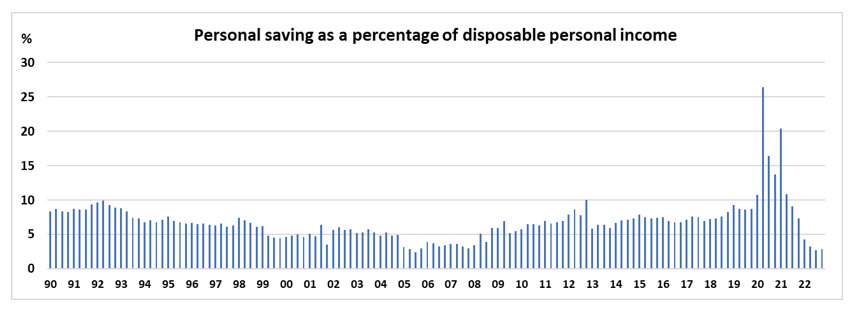

The threat to the economic outlook arises from the combination of declining real household disposable incomes, the erosion of ‘excess’ liquid savings and the less attractive credit terms on offer. An overheated labour market is no protection against a balance sheet recession – affecting property and financial asset prices, triggered by inadvertent quantitative tightening. The Fed may go easy on funds rate increases from here, but beware its passion for QT.

Figure 1:

Data source: US Federal Reserve, table H8

Figure 2:

Data source: US Federal Reserve, table H8

Figure 3:

Data source: US Federal Reserve, table H8

Figure 4

Data source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NPIA tables

In an interconnected world, should we be looking at the Fed in isolation, or would it be better to look at some composite of the major Central Banks – e.g. Fed+ECB+BoE+BoJ? would such a composite have more predictive power?