An endogenous financial system is one in which central banks have become embedded into the machinery of the private financial system, where the structure of interest rates is conditional on the monetary policy regime and where financial system liquidity is inextricably connected to financial asset prices. It is a financial system over which the authorities – national or international – have merely influence rather than control. It is a financial system that is ill-equipped to cope with an inflationary shock of the kind that has recently occurred. It is a financial system that is acutely vulnerable to an interest rate reset. It is a financial system where anything can happen – and will. We stand on the brink of another financial instability event.

Over the past thirty years or so, the western financial system has been in transition from being funded by intermediaries (banks and long-term savings institutions) to being financed by markets. This represents a dramatic reorientation of the financial system from a loanable funds model (lending against deposits and long-term savings) to a credit model (lending against collateral). Whereas deposits and long-term savings can be regarded as capital-certain in most circumstances, collateral – usually real estate or fixed income securities, but sometimes equity – has uncertain capital value.

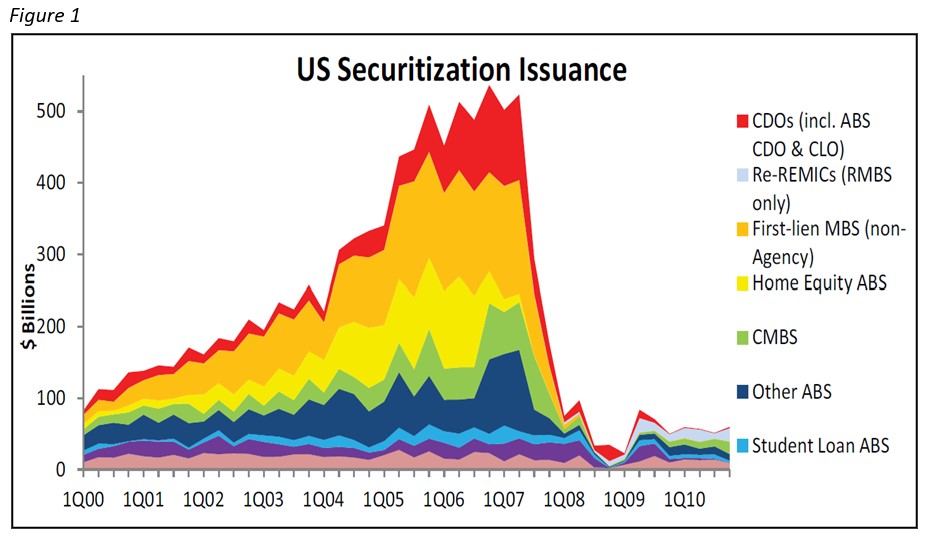

In the old world, (bank) deposit liabilities were the principal source of liquidity for the real economy, property and financial sectors. Financial crises occurred when bank loans went sour, impairing bank balance sheets and inflicting losses on their shareholders. In the new world, aggregate liquidity is provided by the total size of financial intermediary balance sheets, meaning that shadow banks can also trigger financial crises, illustrated in figure 1 by the collapse of US securitisation in 2008. US shadow banks’ marginal source of finance is commercial paper; broker-dealers’ marginal source of finance is the repo, or sale and repurchase agreement. Repo lending rests on the collateral of US Treasury debt.

As Treasury yields fall, bond prices rise and although the par value of collateral underpinning the repo is unchanged, the purchasing power of that collateral rises. When Treasury yields rise, bond prices fall and the purchasing power of underlying collateral declines. Individual Treasury securities have defining characteristics, such as coupon, redemption date, callability and tax status, and are not therefore interchangeable. When shortages develop in a particular Treasury security, the US Federal Reserve lends these securities out to ease market liquidity pressures, also known as renting out balance sheet capacity.

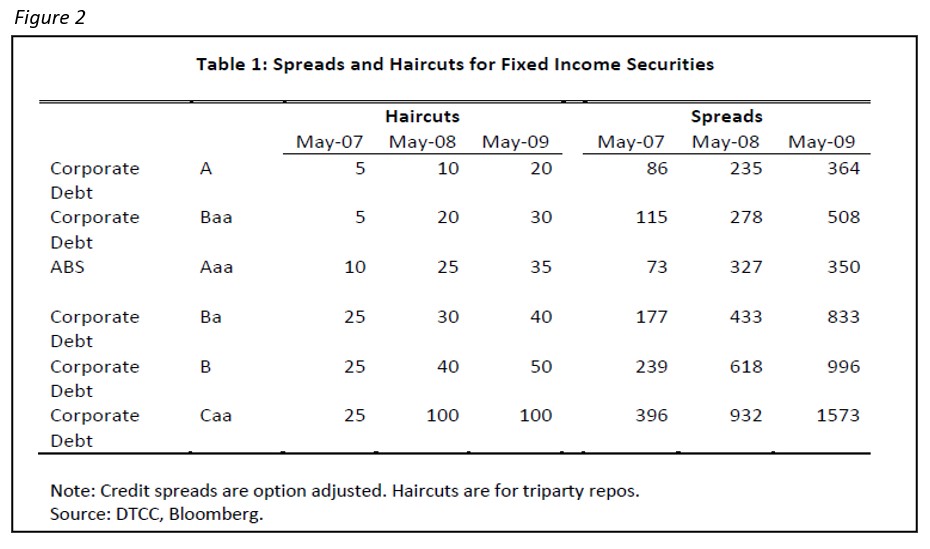

The ultimate liquidity of the financial system is bank deposits at the central bank plus high-quality collateral (securities that can be converted into central bank deposits at no haircut) held by banks. Only banks can undertake this conversion overnight; non-banks cannot change even high-quality collateral into central bank deposits. Lower quality collateral resembles high-quality collateral in good market conditions, but when the heat is on, lower-tier collateral is subject to haircuts. Figure 2 gives a reminder of the evolution of haircuts during 2007-09.

David Murphy, founding partner of Rivast consulting, provides the following insight: One of the complexities of collateralisation is that while, at a micro level, posting collateral protects the postee, reducing direct credit risk, at a macro level “the actions of all collateral takers may create contagion and instability in asset markets both through procyclical margin calls (causing forced asset sales to generate the cash needed to make the call) and through fire sales of collateral portfolios after a default”.

Way back in 2012, Singh and Stella¹ concluded:

“’Monetary’ policy is currently being undertaken in uncharted territory and may change some fundamental assumptions that link monetary and macro-financial policies. Central banks are considering whether and how to augment the apparently ‘failed’ transmission mechanism and in so doing will need to consider the role that collateral plays as financial lubrication. Swaps of ‘good’ for ‘bad’ collateral may become part of the standard toolkit. If so, the fiscal aspects and risks associated with such policies – which are virtually nil in conventional QE swaps of central bank money for Treasuries – are important and cannot be ignored. Furthermore, the issue of institutional accountability and authority to engage in such operations touches at the heart of central bank independence in a democratic society.”

Twelve years on, central bank excursions into unconventional monetary policy have become commonplace and the horizons of moral hazard have expanded significantly. Fiscal and monetary policy have become blurred, particularly in the UK because of the 2012 taxpayer indemnity for Bank of England losses on the sale of gilts. Furthermore, the central banks have facilitated a financial landscape in which private credit has flourished alongside private equity and grown into a US$3trn market.

The catastrophic policy decision to monetise the Covid-19 incremental budget deficits laid the foundations for the 2021-22 inflationary lapse and the inevitable interest rate reset. This had a devastating effect on bond and equity prices in 2022, resulting in a destruction in the purchasing power of high-quality collateral. The ready response of the US and UK governments has been to increase their budget deficits and the pace of primary debt issuance. It is as if the authorities are deliberately manufacturing “high-quality” collateral to compensate for the erosion in the market value of existing collateral, as a means of replenishing market liquidity and supporting nominal asset prices.

The obvious pitfall of this approach to financial stability arises when bond yields spike and buyers pull back from official debt markets. The buyer of last resort is the central bank, that may again be forced to intervene to stabilise government debt prices. But this constitutes another act of monetisation, carrying the risk of further inflation volatility. The bottom line is that the financial system that has evolved cannot tolerate the continuation of interest rates at (or above) their current levels. Come hell or high water, the monetary authorities must engineer a fall in the whole interest rate structure very soon, otherwise things will start to break.

¹Manmohan Singh and Peter Stella, “Money and Collateral”, IMF Working paper WP/12/95, April 2012