Rachel Reeves is rumoured to be considering a change to the government’s public debt ratio target in her 30 October Budget, such that decisions on the scale and timing of the Bank of England’s asset purchases would become irrelevant. The motivation for making yet another change in definition is to allow more room for public investment, the new sacred cow of economic policy. However, making a minor tweak to the fiscal rule is equivalent to a rearrangement of the deckchairs on the Titanic. It would do nothing to alter the woeful trajectory of the UK public finances, nor improve the UK’s economic prospects.

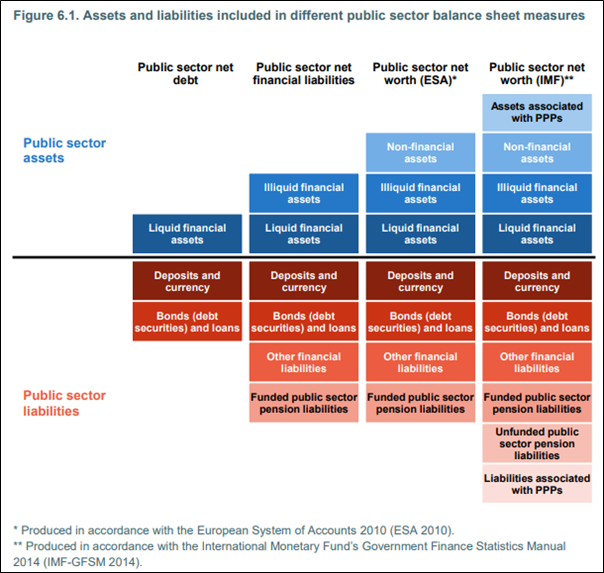

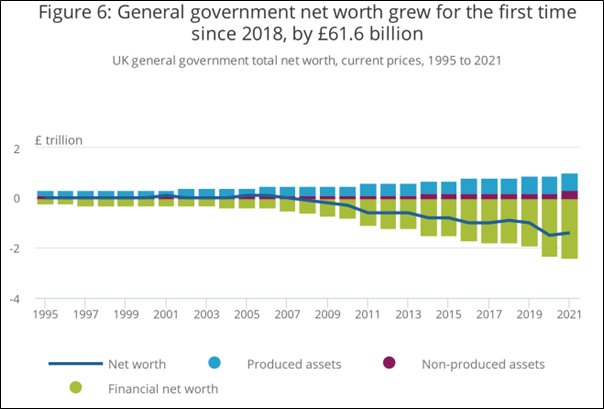

The narrow focus on public sector net debt (PSND), defined either including or excluding the Bank of England contribution, avoids the substantive issues regarding other financial assets and liabilities, pension liabilities (funded and unfunded), and assets and liabilities associated with public-private partnerships (PPPs) (see figure 1). Successive governments have exploited this narrow focus by swelling distant and contingent liabilities that weaken public sector financial health from a broader perspective. According to the latest UK balance sheet data, the general government sector had modestly positive net worth between 1995 and end-2007 (figure 2). The costs of mitigating the impact of the global financial crisis took a heavy toll on the public sector balance sheet, which was in deficit to the tune of £1trn at the end of 2019. The costs of policies implemented during Covid sent net worth even deeper into the red before higher interest rates from 2022 devalued those distant public sector liabilities to deliver a reprieve.

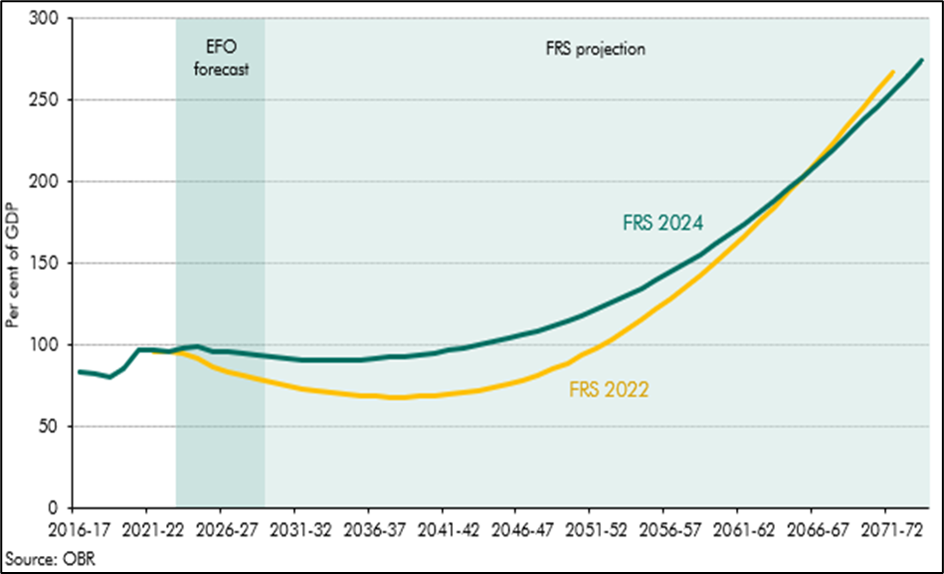

Nevertheless, the structural deterioration of the public sector balance sheet has been reinforced by the shift to larger budget deficits since 2019. The greater the net debt, the larger the net debt service costs. The higher the median age of the population, the greater the automatic government spending. As the population also becomes less healthy and working lives become shorter, then the burden of dependency to be met from the public purse also increases. The long-term outlook for the UK public finances is dreadful (figure 3).

The secular deterioration in the net worth of the public sector has a direct bearing on the achievability of budget balance and on the trajectory of the net debt to GDP ratio. The only proven routes to fiscal stability are the imposition of severe constraints on public spending (including the complete abandonment of some activities by the government), the imposition of new taxes in a form that has little or no impact on national income and the use of financial repression (mainly an enforced negative real return on government securities). A fourth route, promoted by neo-Keynesians the world over, is debt-financed public investment.

The Keynesian argument is that public investment has a long-term multiplier of more than one. Undoubtedly, such investments exist, particularly in the realms of energy, transport and communications infrastructure. However, in highly indebted developed economies, the issue lies in the cost of financing or internal rate of return of the public investment. Most types of public investment fail the multiplier test today, but would not have done so 20, 40 or 60 years ago. A second aspect of the problem with public investment is universality. There are poor regions for which the income multiplier of public investment is comfortably larger than 1, but if the policy is to be applied generally, the aggregate multiplier will be dragged below 1. Third, there is a long history of waste and corruption in the administration of public funds to large projects, which cannot be ignored.

If Rachel Reeves and her Treasury team are serious about economic transformation through public investment, then they should consider replacing the debt-GDP target with a public sector net worth target as considered by Hua Chai, Jason Harris and Alexander Tieman in an IMF working paper entitled “Beyond debt: net worth fiscal anchors”, published in July this year. The following is a quote from their conclusion:

“We find that a net worth target is conducive to public investment and economic growth, particularly in a low interest rate environment. A net worth anchor also precludes explosive debt dynamics and guides fiscal policy to react to changes in the macroeconomic environment, including the interest rate. A net worth target is best used as a medium- to long-term guide to fiscal policy and can be complimented with debt-based considerations over the short-to-medium term. This leaves sufficient room for countercyclical fiscal policy at business cycle frequencies and mitigates the impact of fluctuations of the value of public assets stemming from movements in the exchange rate, interest rate, etc. While the operationalisation of a net worth anchor presents challenges, these are surmountable. Overall, the potential benefit of using public sector net worth to guide fiscal policy over traditional debt-based fiscal rules is substantial.”

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3: Projections of public sector net debt

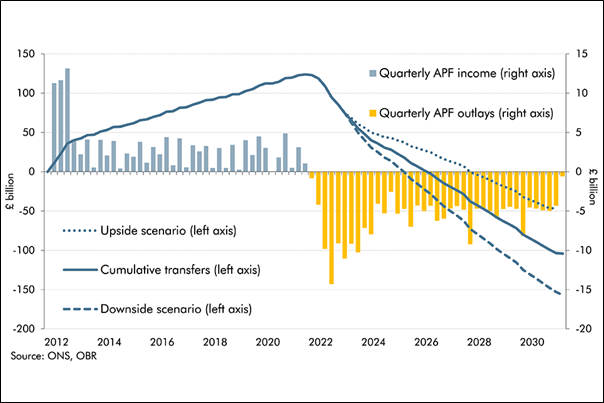

Figure 4

Source: OBR Economic and fiscal outlook, March 2024