There are, broadly speaking, two contrasting approaches to the management of financial stability risk. The first is pre-emptive and preventative in character; the second is reactive and cavalier. After the 2008 crisis, there were high hopes that central banks had switched from the second to the first, but recent evidence contradicts this optimism. At the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, it seems that we have defaulted to reactive financial policy and reactive monetary policy. Reactive monetary policy adopts a whack-a-mole approach to inflation; reactive financial policy aims to out-run the crisis threat, making running repairs along the way.

At Lancaster House, on 25 September 2002, then Fed chairman Alan Greenspan gave a short address entitled, “World Finance and Risk Management”. The tragic events of the previous September, burnt into our collective memories as 9/11, were fresh and raw. His message, if I have understood him correctly, was that private risk markets were better equipped to deal with adverse events than central banks. “The development of our paradigms for containing risk has emphasised, and will of necessity continue to emphasise, dispersion of risk to those willing, and presumably able, to bear it. If risk is properly dispersed, shocks to the overall economic system will be better absorbed and less likely to create cascading failures that could threaten financial stability.”

In the speech he marvelled at the capacity of new instruments – credit default swaps, collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) and credit-linked notes – to mitigate credit risk, especially the massive losses resulting from the over-indebtedness of telecommunications companies (in the wake of 3G auctions) and the reduction in the associated stress on banks and other financial institutions. He went on to praise the absorption of losses resulting from high profile failures such as Enron, Global Crossing, WorldCom and SwissAir, by insurance companies and pension funds. “In particular, the small but rapidly growing market in credit derivatives has to date functioned well, with payouts proceeding smoothly for the most part.”

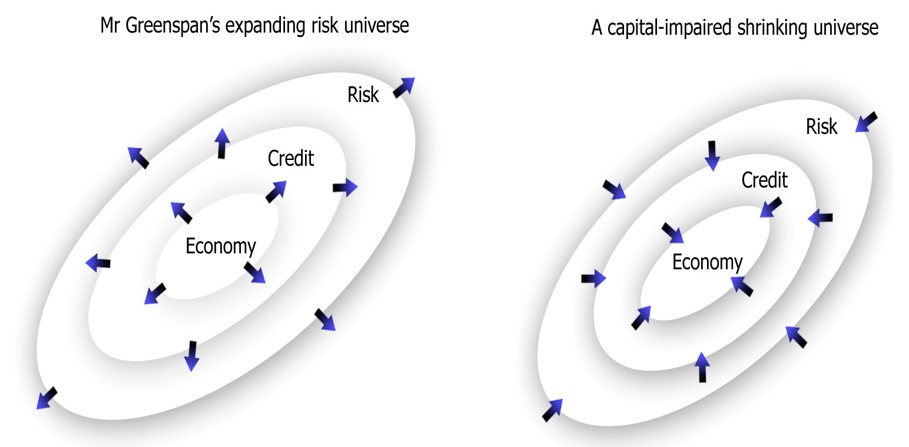

A visual representation of Alan Greenspan’s vision for a robust, vigorous and healthy financial system is shown in the left-hand frame of figure 1. The efficient pricing of risk by well-capitalised insurers and derivative market participants enables concentrations of credit risk to be laid off into these markets, in turn, allowing businesses and consumers to access ample credit at an affordable price, promoting economic growth and full employment.

Greenspan acknowledged that the benefits of risk dispersion would require the deployment of significant leverage, since it was unrealistic for risk-takers to hold massive positions in the underlying financial instruments. “Leveraging always carries with it the remote possibility of a chain reaction, a cascading sequence of defaults that will culminate in financial implosion if it proceeds unchecked. Only a central bank, with its unlimited power to create money, can with a high probability thwart such a process before it becomes destructive. Hence, central banks have, of necessity, been drawn into becoming lenders of last resort.” These implosive dynamics are illustrated in the right-hand frame of figure 1. In his scheme of things, the role of the central bank is to use its unique advantages (including its rock-solid balance sheet) to forestall financial contagion.

There is a telling phrase in the first of the quotations above: “those willing, and presumably able, to bear risk”. Over the past 22 years, there have been repeated instances where leveraged institutions (think AIG) were providing significant risk capacity to the financial system, only to suffer a material re-pricing of their own debt. The likelihood, nay inevitability, of leveraged “insurers” suffering adverse events of their own, constitutes a serious flaw in the Greenspan vision of an ever-expanding financial universe. (There is a clear distinction between unregulated, leveraged insurers with minimal share capital and regulated, public quoted, insurance companies with financial reserves.)

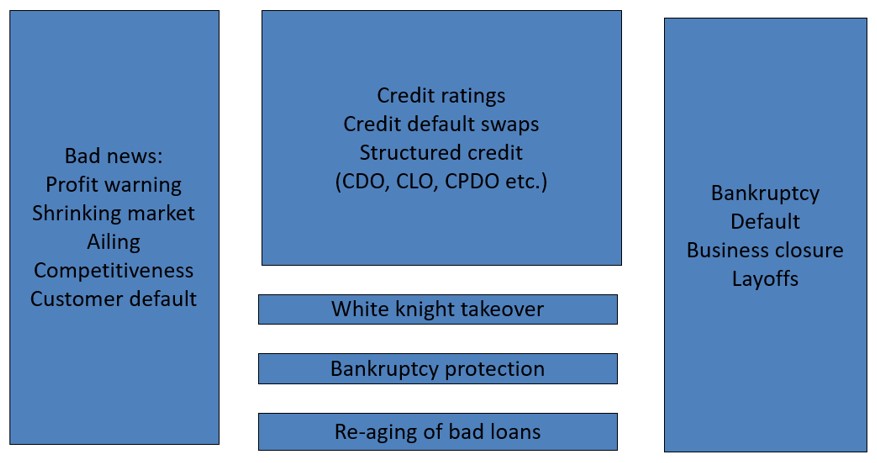

Greenspan’s aspiration for the financial system was that risk mitigation strategies would become sufficiently well-developed to prevent adverse events (e.g. profit warnings, natural disasters, frauds) from triggering hard-edge outcomes (e.g. personal bankruptcies, corporate insolvencies, credit defaults, redundancies and layoffs). He hoped for the development of markets for catastrophic risk (to replace syndicates such as Lloyds-of-London). He dreamt of credit markets that would remain open in all economic climates, for the worst credits as well as the best.

In addition to the new credit instruments that he was so excited about, there were other remedies (see figure 2). First, the white knight takeover, whereby a firm with a strong balance sheet absorbs a failing or failed competitor. Second, the provisions of the bankruptcy code whereby debtors can seek protection from their creditors while efforts are made to restructure the business as a going concern. Third, more controversially, the re-aging of non-performing loans that takes place when they are sold into new ownership.

In the 5 years following Greenspan’s visionary speech – and the soon-to-be unveiled Bernanke anti-deflation toolkit – the US and UK financial systems leveraged-up to the eyeballs and suffered life-changing injuries during the 2007-08 financial crisis. The transition from the left-hand to the right-hand frame of figure 1 was instantaneous and brutal.

Figure 1

Amid fears of an unfolding global depression in early-2009, the Fed and the Bank of England departed from the lender of last resort model and unleashed large-scale asset purchases of government bonds, soft lending schemes and liquidity life rafts to ailing institutions. Central banks transformed into the whitest of all white knights, using their own balance sheets to replace the private sector capacity destroyed by the securitisation crisis.

Figure 2

Why bring up all this ancient history? Because we have arrived full circle, and central bankers have fallen in love with the ever-expanding universe once more. The avalanche of central bank large-scale asset purchases (QE) that occurred in the context of the pandemic sought to prevent a disruptive turn in the credit cycle, but instead made the problem much, much worse, as inflation erupted on a scale unseen for 40 years. The interest reset of 2022-23 appeared to set the seal on an epic credit crunch for the private sector, but the authorities had a few more tricks up their sleeves. Whilst superficially tightening liquidity conditions for the private sector through the unwinding of central banks bond purchases (QT), the US witnessed a drawdown in government (Treasury General Account) cash balances and a liquidation of Reverse Repo ‘sterilisation debt’; the ECB purchased sovereign government bonds outright, as did the Bank of Japan. The Bank of England lent money to banks and the banks bought the government bonds.

Essentially, QE results in the private sector gaining liquidity; QT results in the private sector losing liquidity. The former is strongly associated with rising asset prices, the latter, falling asset prices. The clearest indication that we have been living in a QE world for the past year – and not a QT world – is that financial asset prices have been rising.

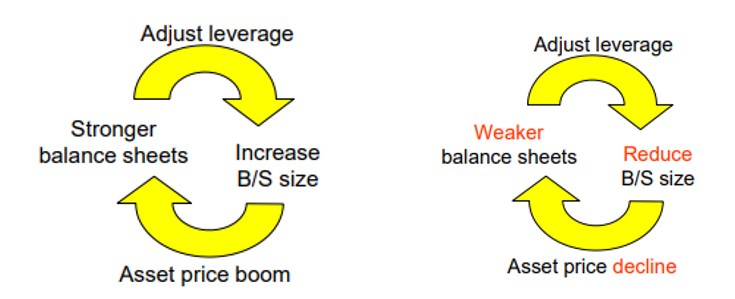

As Tobias Adrian and Hyun Song Shin explained in their seminal paper “Liquidity and Leverage”, (revised version, 2010): “Aggregate liquidity can be understood as the rate of growth of the aggregate financial sector balance sheet. When asset prices increase, financial intermediaries’ balance sheets generally become stronger, and – without adjusting asset holdings – their leverage tends to be too low (figure 3). The financial intermediaries then hold surplus capital, and they will attempt to find ways in which they can employ it. For such surplus capacity to be utilised, the intermediaries must expand their balance sheets. On the liability side, they take on more short-term debt. On the asset side, they search for potential borrowers. Aggregate liquidity is intimately tied to how hard the financial intermediaries search for borrowers. In the sub-prime mortgage market in the United States we have seen that when balance sheets are expanding fast enough, even borrowers that do not have the means to repay are granted credit – so intense is the urge to employ surplus capital. The seeds of the subsequent downturn in the credit cycle are thus sown”.

Figure 3

Another bout of de facto QE, born out of the fear of a destructive turn in the credit cycle with its attendant implications for financial asset prices and for the global economy, has fuelled another aggressive phase of leverage in financial markets, this time propelled by private credit markets, whose activities are not yet adequately captured in the US official statistics. Is private credit the new sub-prime mortgage credit? The potential for a repeat of 2007-08, as the favourable dynamics of the left-hand frame are displaced by the unfavourable ones of the right-hand frame, is obvious to anyone who dares to examine the detailed evidence.