An obscure working paper of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) appears to have become the cornerstone of UK economic policy. A gleeful gaggle of former mandarins, left-leaning academics and investment company executives has rushed to endorse its findings, which confirm what they believed all along, that the key to stronger economic growth is a sizeable boost to (tangible) public investment. As is so often the case in economics, seemingly straightforward and sensible propositions prove to be anything but. The source of financing of public investment is fundamental to its efficacy. In a highly-indebted and encumbered financial system, there are sound reasons to expect that additional debt-financed public investment will not enhance the outlook for economic growth.

The OBR’s DP no. 5, entitled “Public investment and potential output”, landed in the public domain in August, a month after the election of the Labour government. Just possibly, it was a coincidence. The central result of the analysis, using a partial equilibrium framework, is that a sustained increase in public investment equivalent to 1 per cent of GDP (about £28bn at current prices) could boost the level of potential output by 0.4 per cent after 5 years, and by about 2.4 per cent at the 50-year horizon. In the chapter that follows these encouraging modelling results, the authors explain that there are four “further considerations” we would encounter when faced with changes in planned levels of public investment:

- the type of assets to be purchased, including the distinction between economic infrastructure (e.g. roads, railways, airports, and utilities, such as sewerage and water facilities) and other types of public investment;

- the mode of investment, including whether to distinguish between direct investment in public sector assets and support for investments that are held privately;

- any general equilibrium effects, including those potentially arising from the choice of financing and from impacts on the supply of other factors of production;

- the delivery and effectiveness of public sector investment.

These considerations are critical to the growth impact of public investment, to the extent that the range of outcomes around the OBR’s central result is extremely wide, encompassing some significantly negative outcomes at the 5-year horizon. The paper quotes a 2021 analysis by the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which found that for changes in US Federal government investment spending financed by additional borrowing, the level of GDP was unchanged at the 30-year horizon, “as higher borrowing led to higher interest rates, which offset the effects of the additional investment via “crowding-out”, where increased interest rates offset the boost to GDP from the additional public investment by reducing funds available for private investment”. Similar difficulties arise with corporate tax-financed public investment.

Aside from the practical obstacles to the delivery of a favourable impact on GDP from additional public investment, there is a fundamental empirical objection to the hypothesis linking levels of public fixed capital formation to the growth outlook. We find that the real rate of expansion of domestic non-financial debt has a much closer relationship to the rate of economic growth than the rate of fixed investment, whether public or private. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, there was a much clearer sympathetic relationship between credit growth and the growth of physical investment than there is today, fostering an ambiguity of causation. Since the mid-1990s, credit growth and the rate of fixed investment have diverged markedly, as credit has been deployed in many different economic and financial contexts, and corporate investment has diversified into intangible assets. We assert that derivatives of the debt stock and other dimensions of the credit system offer a superior explanation of variations in GDP growth to one based on a production function (with labour and fixed capital as the factors of production).

In a 2016 Economic Perspectives research paper, we discovered that a tight-fitting explanation of global GDP, based solely on the dimensions of the global credit system – its quantum (public and private), credit spreads and Treasury yield curve slope. We found that private debt was more than 3 times more powerful a stimulant of GDP than public debt; that widening credit spreads exerted a powerful dampening impact on GDP and that a steepening of the yield curve strengthened GDP.

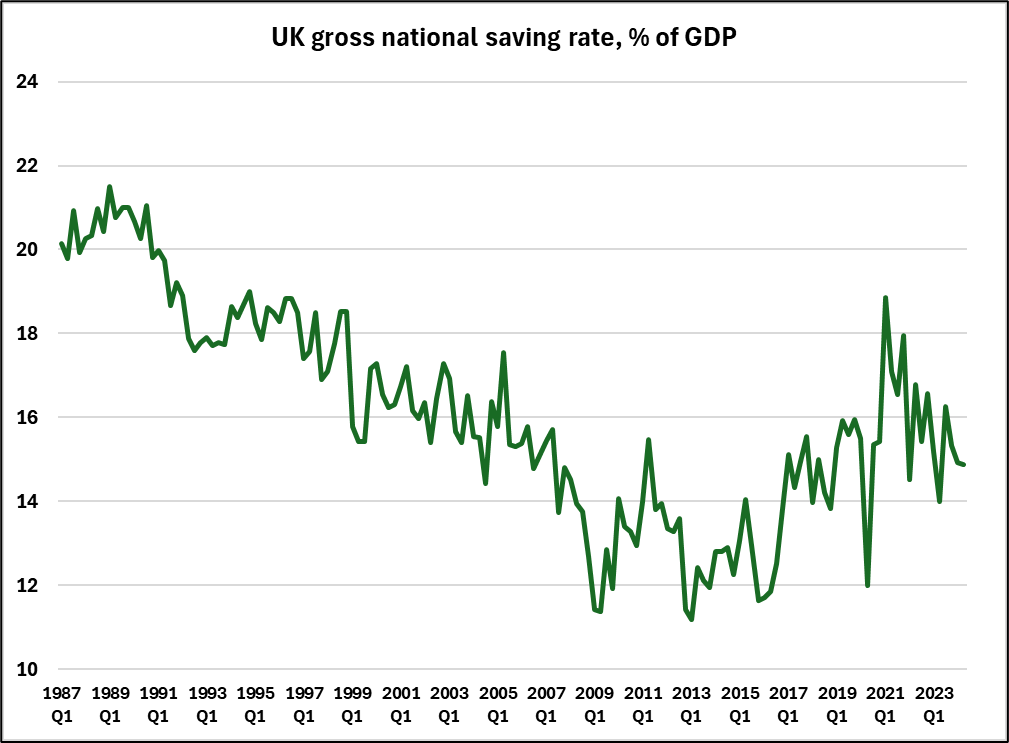

A healthy credit and financial system, in which varying levels of interest rates act to discipline the use of financial resources and where real interest rates and the real GDP growth rate do not deviate materially over long periods of time, promotes healthy rates of national saving and fixed investment. The low rates of national saving and fixed investment typically observed in the UK over the past 20 years (figure 1) are by-products of an errant monetary policy regime, consisting of artificially low interest rates and financial repression.

In summary, today’s “growth problem” is at root a debt saturation problem. We have overcommitted future income streams to debt service, leaving too little scope for consumption sacrifice in favour of expenditures on enhancements to human and non-human capital, the activities that provide the source of larger future income streams.

Figure 1

I wondered for a moment if you were suggesting a “debt jubilee”.