Last week’s Budget takes its place in the growing catalogue of exercises in national self-harm. Our reckless credit bingeing in the mid-2000s set us up for a post-GFC hangover; Brexit opened up a world of pain rather than a world of trade; the illiberal response to the Covid pandemic, involving multiple lockdowns and the abominable waste of public money, landed us with a stack of debt, snuffed out half a million small businesses, undermined our work ethic and crippled the national health system. Not to be outdone, Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have jacked up employment taxes and doubled down on the iniquities of inheritance tax. Our beleaguered private sector has scarcely recovered from one blow when another knocks it flat. A stiff upper lip and self-deprecating humour are fair enough, but surely, self-mutilation carries a sense of Britishness too far. Perhaps we were hoping for national self-harm to be included in the next Olympics?

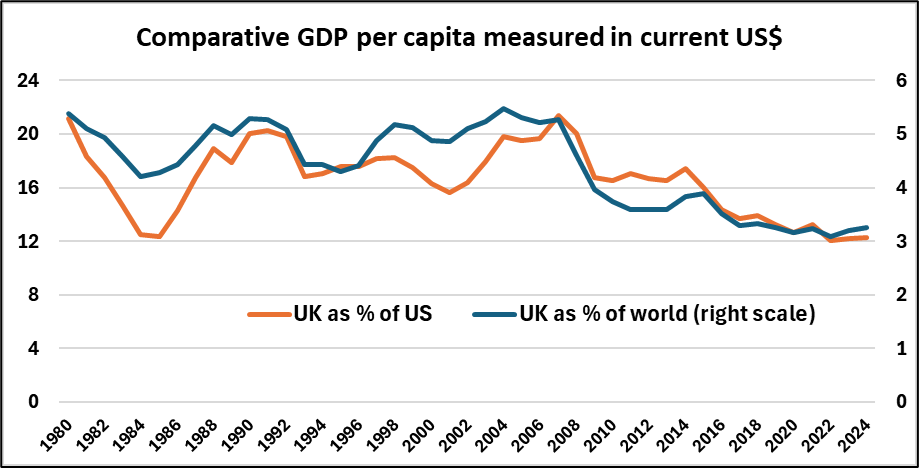

It is worth reminding ourselves (figure 1) that in 2006 the UK had a global GDP per capita share of 5 per cent and was more than a fifth of the size of the US economy. In 2023, the comparable figures are 3.25 per cent in relation to the world and one-eighth the size of the US. These comparisons reflect a mixture of real growth differentials, inflation differentials and changes in the external value of Sterling. In 2006, the UK ranked 9th in the IMD Global Competitiveness Index, a comprehensive index that considers a nation’s institutions, policies and other factors that affect productivity. By 2021, the UK had slipped to 18th place, to 23rd in 2022, 29th in 2023 and 28th in 2024. While part of our relative decline is undoubtedly attributable to the rapid growth of the Asian economies, a sizeable chunk represents our own folly and fecklessness.

Figure 1

Data source: IMF

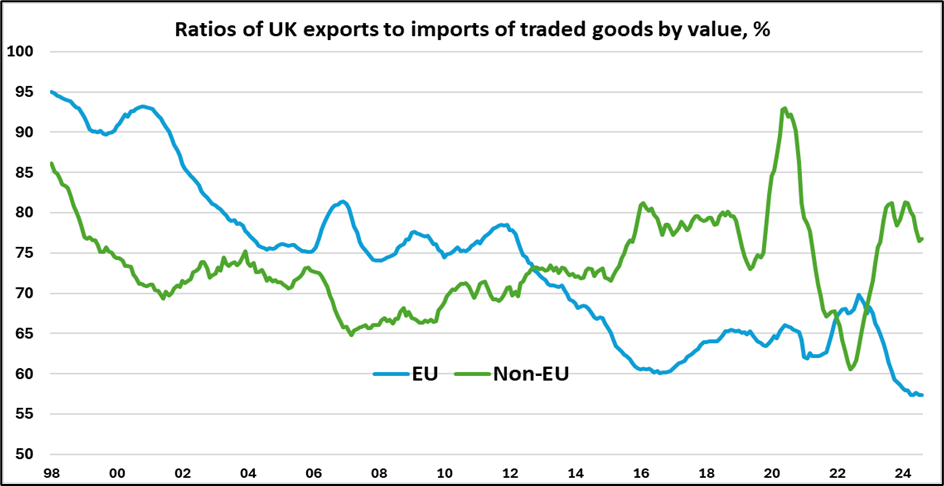

It is unnecessary to rake over the ashes of the GFC, other than to note that the UK economy was relatively hard hit on account of its outsized banking and financial sector and its degree of international openness. The UK’s acrimonious withdrawal from the EU has failed to yield the hoped-for tangible trade benefits, the UK has been excluded from many European supply chains and, arguably, the EU has exacted retribution on the UK through studied non-co-operation. In terms of visible trade, the ratio of UK exports to imports vis-à-vis EU has resumed a downward trajectory post-Covid, while the comparable ratio for non-EU countries has settled back in a similar range to that in 2015-19. It can be argued that too little time has elapsed (since 31 January 2020) to draw any firm conclusions about the impact of Brexit on international trade, but it is difficult to point to any breakthroughs in trade agreements that would justify an optimistic outlook.

Figure 2

Data source: ONS national accounts

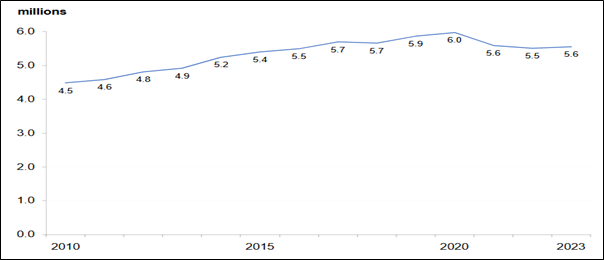

Appreciating that this is far from the consensus view of the appropriateness of Covid restrictions on economic activity and freedom of movement, there is powerful statistical evidence to suggest that the second and third UK lockdowns were a monumental error of public policy. There was a dichotomy between the pandemic support provided for employees versus the self-employed, whose businesses failed in large numbers. Figure 3 shows that the small business sector has not recovered from the Covid shock. The legacy of the Covid response spans the fall in public sector productivity, the worst inflationary episode in 40 years, the massive increase in public sector debt and the costs of debt service and the crippling impacts on the national health and social care systems.

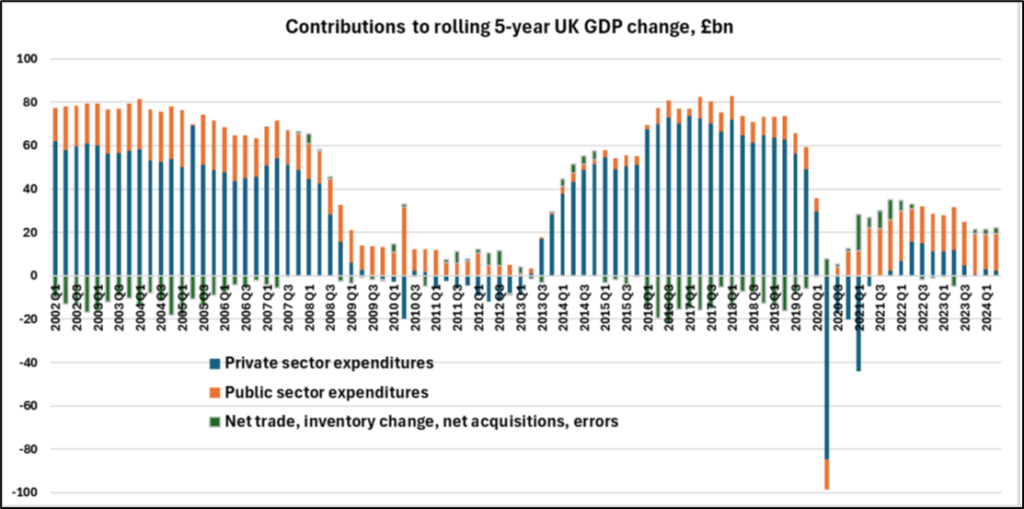

The determination of the previous government to avoid a meaningful recession in 2023 led it to ratchet up public spending and borrowing once more. Over the past 5 years, virtually all the meagre growth of the UK economy has been contributed by public sector expenditures (figure 4). And now, we have a Labour government that has declared its intentions to focus even more resources on the public sector, financed by a mixture of employment and capital taxation and fresh borrowing. The reaction of many businesses to the elevated tax burden will be to shrink or to close. A private sector recession is on the cards for 2025-26 unless looser monetary policy comes to the rescue.

In summary, through a series of profound policy errors over the past 20 years, the UK has squandered its position in the global economic pecking order. We have forfeited our dynamism, ebullience and entrepreneurial spirit, and ironically, in the context of Brexit, we have drifted towards the social democratic models of our stagnant continental European neighbours. The UK is ripe for another policy revolution.

Figure 3: Number of private sector businesses in the UK, 2010-2023

Source: Department for Business and Trade

Figure 4

Data source: ONS national accounts