A previous comment noted the scandalous decline in UK net national saving. Armed with the full data set for 2023 and substantial information on the first 9 months of 2024, the situation remains deeply concerning. Net national saving was zero in 2023 and is heading for around 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2024. In 2023, net national saving by companies and households amounted to 2.5 per cent of GDP and was fully offset by public sector dissaving. Last year, the public sector offset was a little smaller, allowing net national saving to turn slightly positive. The households saving rate rebounded, spurred by 4 per cent interest rates on deposits, but corporate savings languished. The corporate sector’s gross saving is almost completely absorbed by the costs of capital consumption. Why has the corporate sector ceased saving?

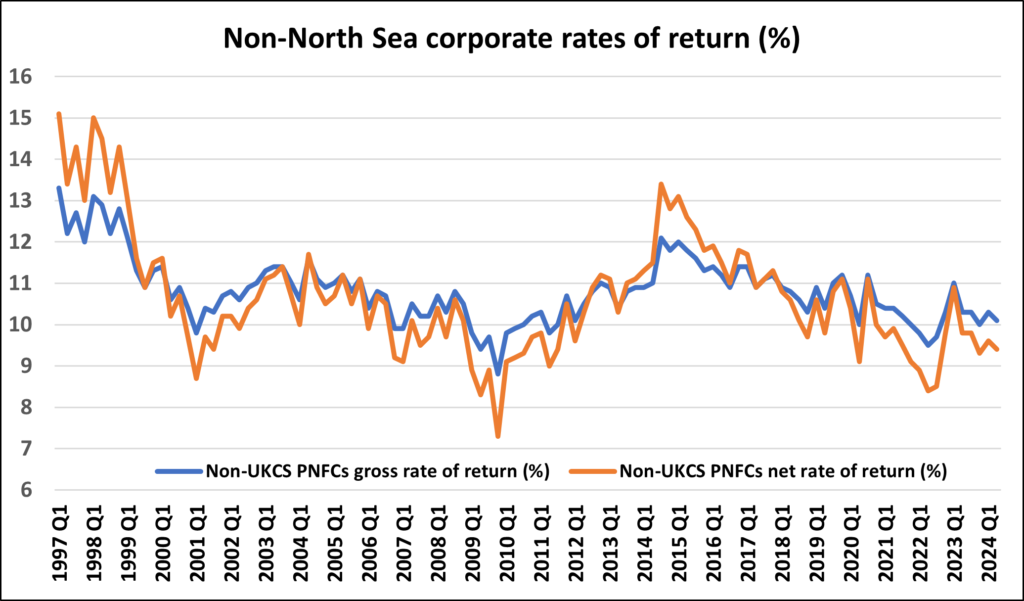

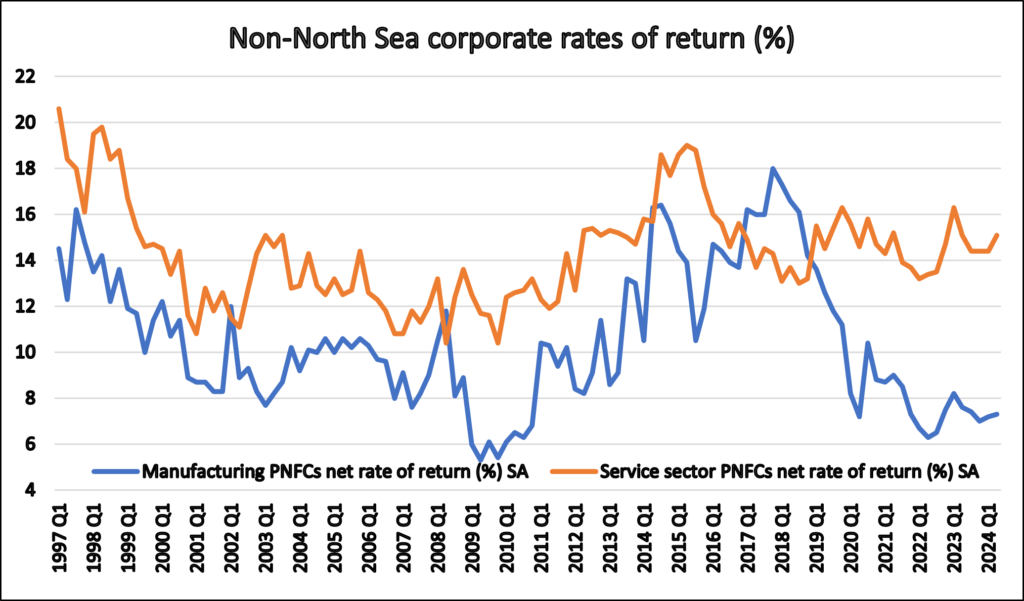

A loss of non-North Sea profitability helps to explain a downshift in non-financial corporate saving after the 1990s, but there is no evidence of systematic deterioration in aggregate profitability thereafter (figure 1). However, there is a noticeable divergence between the rates of profitability in the services and manufacturing sectors (figure 2). One hypothesis is that the manufacturing sector retains more capital (distributes less capital) than the service sector.

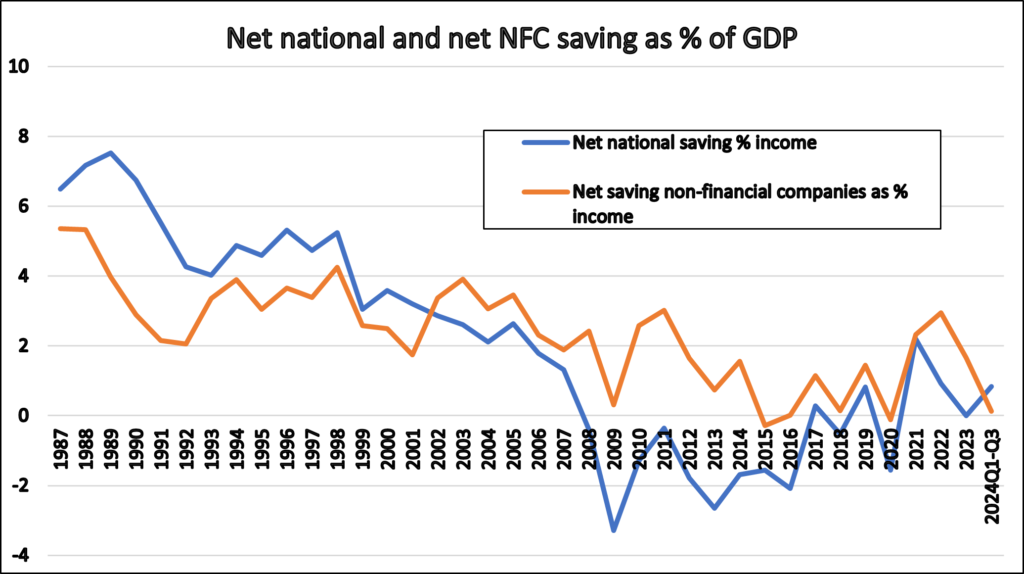

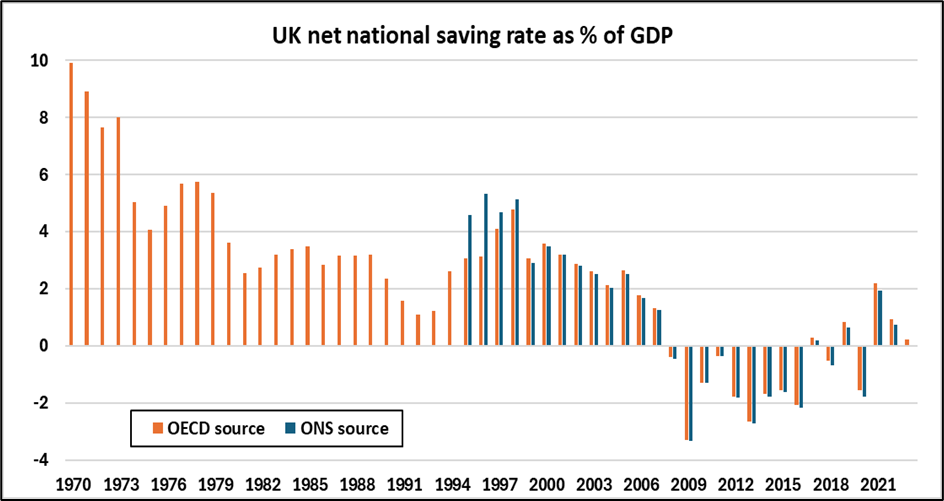

While there is a clear downward drift in the net saving rate of non-financial companies, from around 4% of GDP in the 1990s to virtually zero in the mid-2010s, the 2008 global financial crisis is easy to spot (figure 3). The GFC constitutes a profitability shock that was concentrated in the manufacturing sector but triggered a swathe of government interventions that sent the public sector deep into deficit (dissaving). It is interesting to note that net national saving recovered steadily in the decade following the GFC, but corporate saving did not – and has not. A longer view of UK net national saving is shown in figure 4.

One credible explanation is that businesses became accustomed to very low borrowing costs after 2009 and learned to operate with credit lines rather than liquid balances, which were also very low yielding. The drawback to this new age of balance sheet management is revealed when there is an abrupt reset of interest rates and the options to refinance borrowings are severely curtailed. Whereas the US corporate sector has been very well insulated from the 2022-23 interest rate hike, UK businesses appear to be suffering to a greater extent. Another important compositional point is that profitability has become highly concentrated, leaving a long tail of weakly profitable and loss-making businesses.

The October Budget has clearly negative implications for corporate profitability across the size spectrum. Given that the government is not focused on the reduction of the structural budget deficit, there is a risk that the net national saving rate will fall in 2025. The government has a great deal of debt to finance in 2024-25, just short of £300bn. If the net national saving rate were to rise from near-zero to just 3 per cent of GDP, that would represent an extra £80bn of domestic saving to help absorb the issuance and keep a lid on gilt yields. We need an urgent revival of corporate saving.

Figure 1

Data source: ONS

Figure 2

Data source: ONS

Figure 3

Data source: ONS

Figure 4

Data sources: OECD and ONS