In June 2016, 37.4 per cent of eligible voters (17.1m out of 46.5m) voted in a referendum to take the UK out of the EU. In November 2024, 31.8 per cent of eligible US voters (77.2m out of 242.6m) voted for a president whose avowed intent was to impose tariffs on its trading partners in violation of international agreements. In essence, a move that might well precipitate the exit of the US from the rules-based global trading system stewarded by the World Trade Organisation since 1995, and previously by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade since 1948. For Brexit, read Yanxit.

As things stand, by applying tariffs unilaterally on all countries on 2 April, the US Administration has reneged on its international obligations. According to Alan Wolff, a former deputy director of the WTO, it is likely that some, even many, of its members will file WTO dispute settlement cases against the US that will most probably succeed. The US would doubtless appeal any adverse findings to the Appellate Body, in the confident expectation that no sanction would follow: the body ceased to operate 5 years ago when the US blocked appointments to it. Stir into the mix that the US is currently delinquent in the payment of its dues to the WTO, and President Trump has set a course that leads inexorably towards the complete withdrawal of the US from the WTO, or Yanxit.

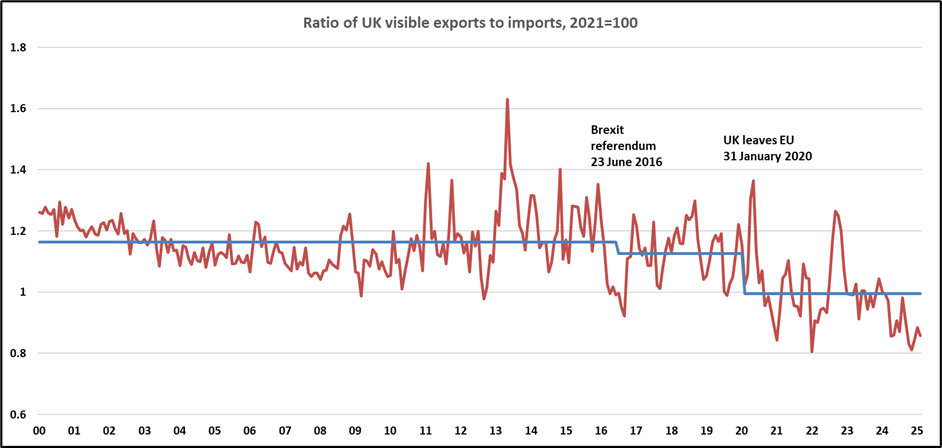

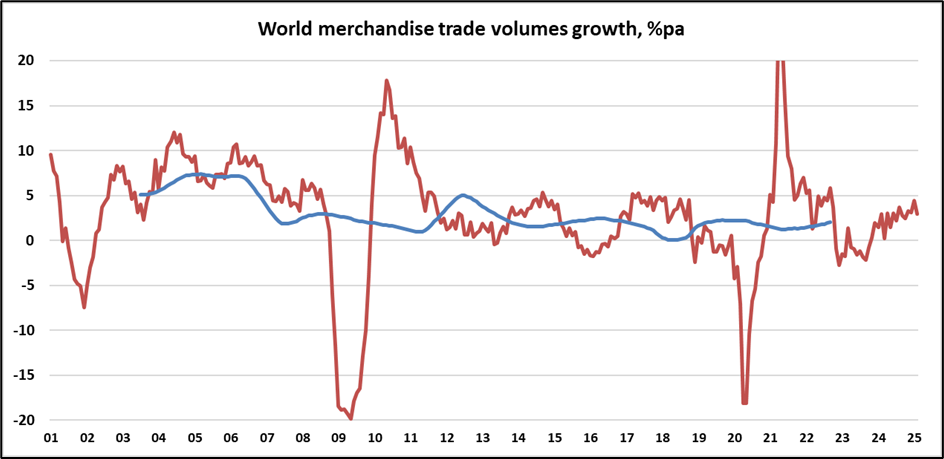

It is extraordinary, to say the least, that the fallacious arguments that featured in the Brexit campaign should be regurgitated 8 years later for the benefit of disgruntled US citizens. The foremost fallacy of the Brexit campaign is that leaving the EU would free the UK to negotiate more favourable trade deals than could be obtained while remaining in the EU. In 2016, it was already clear that the political path of least resistance in matters of international trade led towards the repudiation of existing agreements, not the granting of new concessions. Brexit gave opportunity for nationalistic and populist sentiments to surface at the UK’s expense, not advantage. Figure 1 documents the realised UK trade performance. Figure 2 shows the deceleration of world trade volumes over the past 20 years.

Whereas the UK limited its actions to the withdrawal from a 19-country customs union and single market, the US has gone much further by the application of tariffs on all its trading partners, amid accusations of cheating and foul play. If the consequence of Brexit was the exclusion of the UK from European supply chains, then the potential consequence of Yanxit is the exclusion of the US from global supply chains.

On a personal note, I am no fan of the European project. In the specific matter of the UK’s membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, the precursor to the Euro, I was vehemently opposed. With Tim Congdon, Bill Martin, Patrick Minford, Gordon Pepper and Alan Walters (collectively known as The Liverpool Six), I was a signatory to a series of letters to The Times, arguing in the strongest terms against this policy, between 1990 and 1992.

While I recognised that, by 2016, the expansion of the EU had progressively eroded the free trade benefits to the UK relative to its net financial contribution, there were still intangible benefits to the UK from EU membership, such as common product standards, co-operation in policing and security, access to a skilled European workforce and the sizeable benefits to London as the foremost European financial centre. The UK was thriving as a frequently dissenting voice within the EU: “in, but nearly out”. The false premise of Brexit was that we could be “out, but nearly in”. This was never an option. Once out, the UK was out-out. (Micky Flanagan joke)

The fallacy of the Trump administration’s tariff policy, in this regard, is to believe that one country, however large and important, can re-order the global trade landscape to its own advantage. Many fail to appreciate the complexity – and beauty – of intricate global and regional supply chains and networks that have evolved over 50 years of a liberal trade order. Hence, beyond the obvious short-term dislocations, they have no conception of the far-reaching consequences of exclusion from supply chains, and the need to build expensive replacements. Domestic consumers suffer a welfare loss, through paying higher prices and through a limitation of choice.

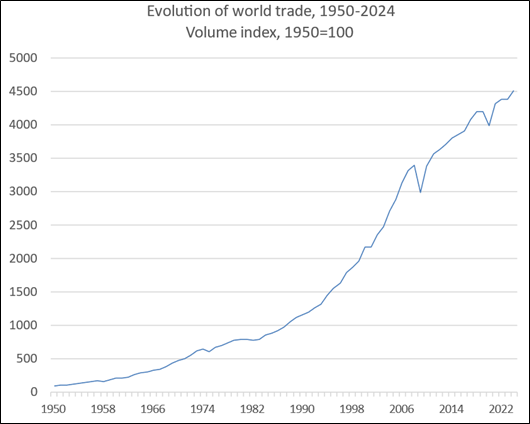

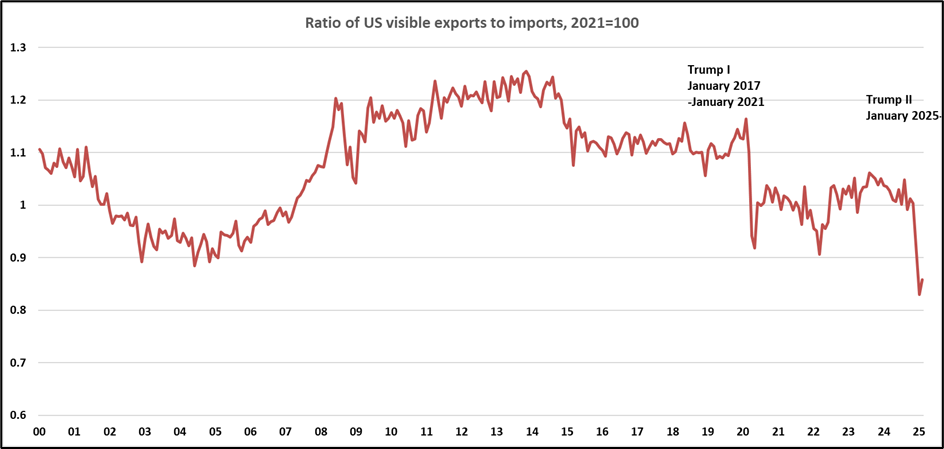

There is a short window – of weeks, not months – for the US to abandon the tariff strategy altogether and provide its best assurances that there will be no repetition of this sad chapter. That ripping sound you can hear is the tearing of the delicate fabric of world trade based on the tariff and non-tariff trade concessions negotiated many years ago, which facilitated an era of nearly-free trade and delivered a tremendous boost to post-war global economic growth (figure 3). In an age of mutual suspicion and a fracturing of the geopolitical landscape, the most likely outcome of a unilateral tariff strategy is that everyone loses, but that the US suffers the most (figure 4). Furthermore, the US has handed strategic geopolitical advantage to its greatest adversary, China, which is eager to insert itself in the gaps created by US introversion.

Figure 1

Data source: CPB

Figure 2

Data source: CPB

Figure 3

Data source: WTO

Figure 4

Data source: CPB

*Image by xadartstudio on Freepik