Peter Warburton – October 6, 2021

2020 was a blow-out year for public sector deficits. The unweighted average budget deficit of the 43 countries listed at the back of The Economist was 8.3 per cent of GDP last year. Similar-sized deficits were recorded after the GFC and the process of dragging the number back to respectability took several years in most cases. Today, governments are planning for a much swifter return to financial health based on the unusually sharp rebound in economic activity. Who benefited the most as government finances deteriorated? Politicians will always claim that individuals were the intended targets, but the UK record shows that private non-financial companies claimed a third of the bounty. Corporate profits are in the firing line as the public finances improve.

Every one of the 43 countries listed in the table at the back of The Economist ran a deficit in calendar 2020, ranging from the abstemious Norway (1.3 per cent of GDP) to the profligate US (14 per cent) and UK (12.7 per cent). The unweighted average deficit was 8.3 per cent of GDP, which is expected to fall to 6.1 per cent in 2021 and more dramatically in 2022. As the tide goes out on pandemic-related government largesse, what will be washed up on the beaches?

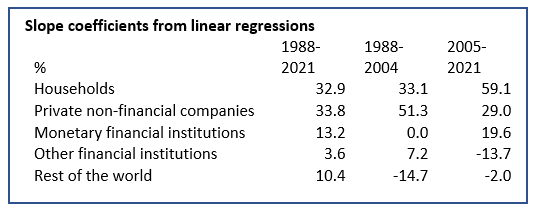

According to the identity in the UK national accounts when the government runs a financial deficit someone else runs a surplus. The full list of counterparties is households, non-profits serving households (NPISH), public sector non-financial companies, private sector non-financial companies, monetary financial institutions, insurance companies and pension funds, and other financial institutions and financial auxiliaries. In addition to these domestic counterparties, there is the overseas sector. Using simple regression analysis, what can we learn about the historical relationship between the government’s financial account balance and those of its counterparties?

Figure 1 shows the slope coefficients (sign reversed) from a linear regression of each sector’s financial balance (net lending (+), net borrowing (-)) on the central government balance. For the full sample, both households and private non-financial companies record a coefficient of roughly one-third, meaning that for every £1bn increase in the budget deficit, these two sector balances each improves by £330m. Banks and building societies score 13%, other financial institutions, 4% and the overseas sector, 10%. When the sample is split in half, the more recent observations support a larger share of the bounty for households (59%) and banks (20%), with other financial institutions and the rest of the world turning negative. The corporate coefficient was broadly unchanged at 29%.

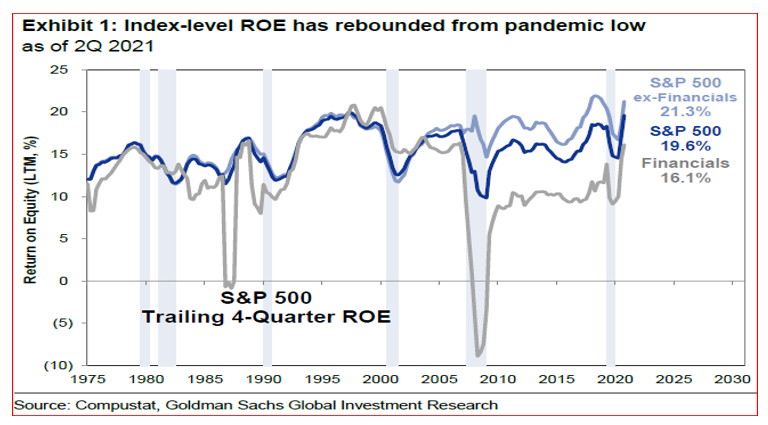

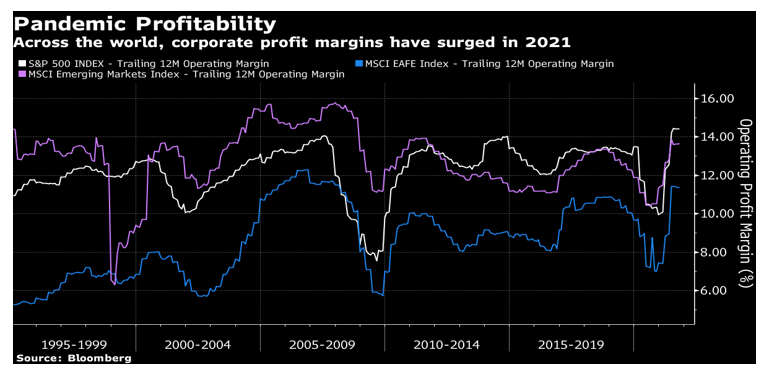

Around the world corporate profitability has rebounded dramatically in recent quarters, beating even the most optimistic expectations, as confirmed in figures 2 and 3. In the UK, the private non-financial company sector rebounded from a financial deficit of £12bn in 2019, to a surplus of £23bn in 2020 and an annualised pace of £36bn in 2021 H1. If the budget deficit were to contract by £200bn from the £274bn peak in 2020, this would imply a £60bn plunge in the corporate balance and an abrupt reversal in measures of corporate profitability. Perhaps we will not see the surge in business capex in 2022-23 that we would normally associate with profits at this level.