Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s 2022 Mais Lecture, like many before it, has highlighted the UK’s productivity challenge. Regrettably, that challenge is even more daunting than before the arrival of the pandemic. Despite the recent restoration of the pre-Covid benchmark for national output, the commercial infrastructure of the economy is noticeably weaker. However much the government may wish us to believe that our economy has regained its prior composure and momentum, like a fallen rider re-mounting his horse, the detailed figures tell a very different story. Repeated shutdowns have taken their toll on private sector productivity, leaving the economy less able to meet the enormous public cost of pandemic support.

The central argument is that the significant expansion of the public sector and the frenzied activity in residential property markets, aided by the extended Stamp Duty holiday for smaller transactions, have twisted the structure of the UK economy and distorted the comparisons. Using some simple deductions from the national accounts, I arrive at the conclusion that private sector output is still between 3.5 per cent and 7 per cent short of its 2019Q3 benchmark. With the publication of estimates for fourth quarter national accounts aggregates and for employment by industry, some crude calculations can be made of the extent of recovery in output per head.

I hesitate to label this measure as productivity, because part of GDP is an imputation of the services rendered to owner-occupiers of their homes. Arguably, those services have been enhanced by the experience of government-decreed lockdowns. For many, the home has become an auxiliary workplace, and for some, the primary workplace. This has provoked a flurry of home improvement as well as an increment to house-moving activity. In 2020, residential property transactions leapt by 27 per cent, but have settled back to their prior trend in recent months.

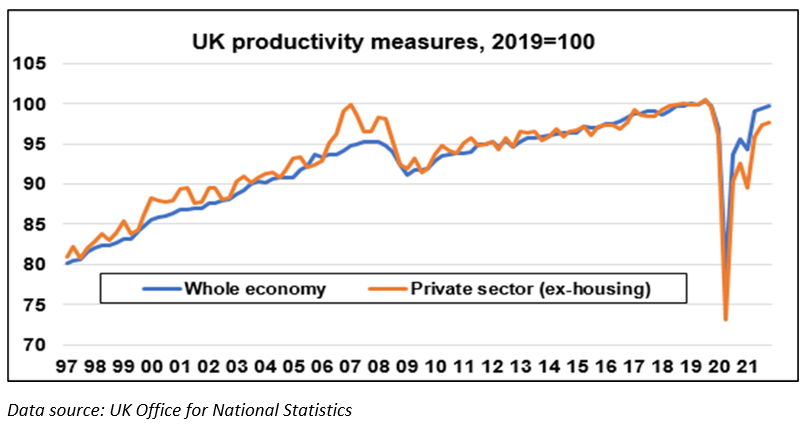

Figure 1 attempts to tease out the underlying behaviour of private sector output per head (excluding imputed services from housing) in the past 2 years. In the final quarter of last year, I estimate that there was a productivity shortfall of 3.5 per cent, compared to the previous growth trajectory – an annual rate of 0.8 per cent per year. The shortfall in productivity is compounded by the fact that private sector employment remains more than 1m lower than 2 years ago. There are some striking sectoral deficiencies: manufacturing employment is more than 10 per cent lower than the pre-pandemic level. In accommodation and food services, the reduction is 7.8 per cent, in wholesale, retail and repair of motor vehicles, 7.6 per cent, and construction, 6.6 per cent. Employment in information and communication is up 8.1 per cent, financial services 7.2 per cent and professional and scientific services, 6.1 per cent.

Meanwhile, public sector employment has swelled by 543,000 with a 15.6 per cent increase in the category of public administration and defence. One of the unanswered questions emerging from the pandemic-induced structural distortion of spending patterns, is the extent to which the state will shrink in 2022-23. If Rishi Sunak is to pull the public finances back into shape, a significant retreat in public spending is essential. Significant segments of private sector activity are really struggling to regain the lost ground. That struggle will intensify in 2022-23 and the lurch toward big government will be much harder to reverse in the context of slow growth.

Figure 1