Since Covid struck, UK public finances have been on a war footing. The usual controls on public spending were relaxed as a matter of expediency, and tens of billions of pounds have been lost to waste, carelessness, and fraud as a result. Furlough payments and energy subsidies have reset public expectations of the role of government in stabilising household financial circumstances and broadened the horizons of moral hazard. The challenge of bringing the budget deficit under control has been undermined further by a broad intellectual shift away from fiscal conservatism. Bold experiments are the order of the day. As another Budget Day approaches, expect the government to row back on the swingeing increase to Corporation Tax in the Autumn Statement, despite the absence of a credible deficit reduction plan.

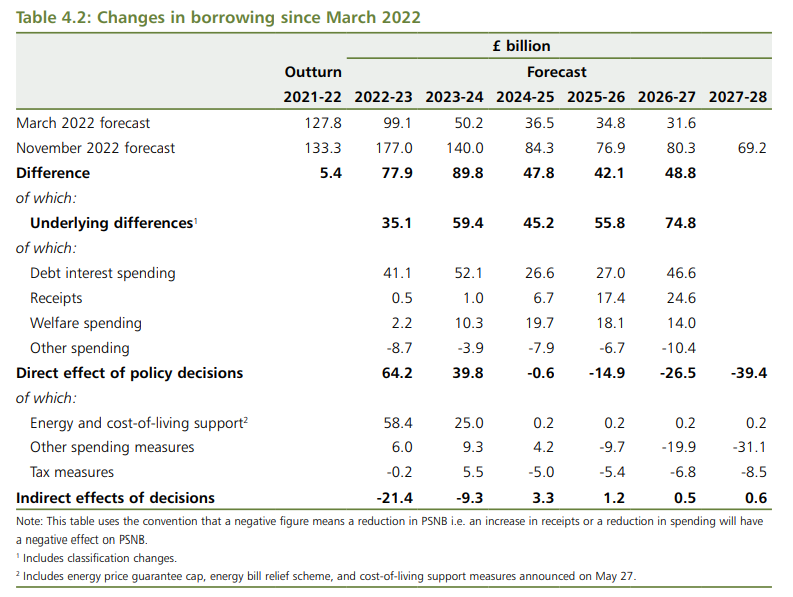

It is becoming increasingly difficult to know how things stand with the public finances. A year ago, as the economy was still re-opening after lockdown restrictions, public sector net borrowing (excluding public sector banks) was expected to fall to £99.1bn in 2022-23. When the Autumn Statement was presented in November, the projection rose to £177bn (figure 1). Energy and cost-of-living support payments contributed £58.4bn, additional debt interest payments, £41.1bn, with some offsetting indirect effects lowering the total difference. Both the energy and debt interest payments have fallen well short of these estimates, delivering a probable budget deficit outturn in the ballpark of £145bn. Incidentally, even the November estimate of the 2021-22 deficit (£133.3bn) has since been revised down to £122.4bn or 5.2 per cent of nominal GDP.

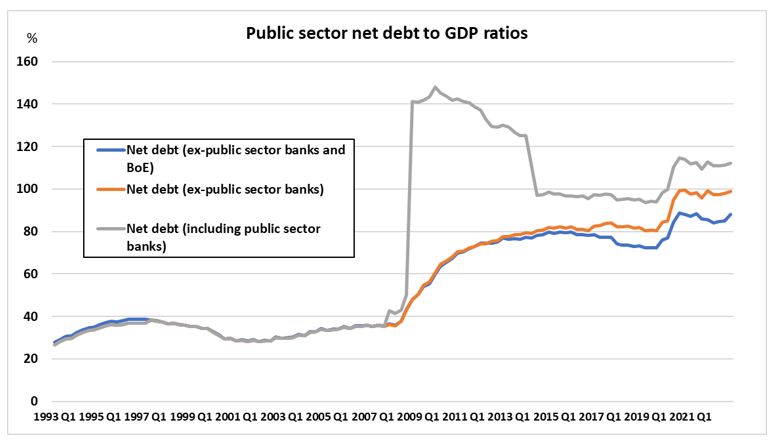

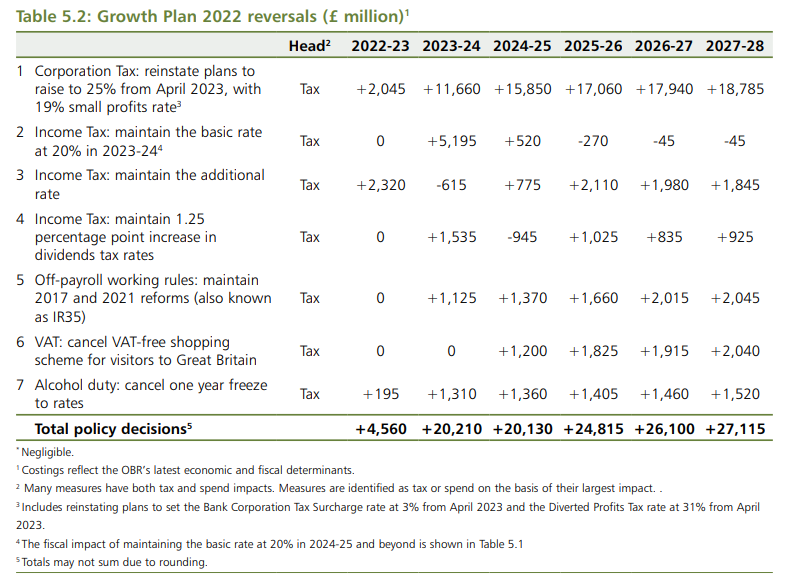

The scale of the programme spending shortfalls smacks of poor design, even a scattergun approach. One of the reasons that support programmes undershoot is that many people are ashamed to claim what is due to them. This ruse of kitchen-sinking the public deficit projections has the convenient corollary of generating a pot of “savings”, to be redeployed as tax cuts or spending commitments at the next opportunity. However, the reality is that the public finances are still in bad shape: £145bn is 5.8 per cent of nominal GDP. Consensus estimates for the deficit in 2023-24 remain clustered around the Autumn Statement projection of £140bn. The net debt ratio is heading north again (figure 2). Before the chancellor rips up another set of budget measures – by postponing or cancelling the revenue-raising Corporation Tax increase that was reinstated in November (figure 3) – he should reconsider the scale of the task of normalising the public finances in the context of the UK’s structural challenges – a drop in labour productivity and participation. Unless the Bank of England is bluffing about its plans for ongoing balance sheet shrinkage, then the funding of perennial deficits equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP will become increasingly problematic and disruptive.

Figure 1:

Source: HM Treasury, Autumn Statement, November 2022

Figure 2:

Data source: Office for National Statistics

Figure 3:

Data source: HM Treasury, Autumn Statement, November 2022