Earlier this month, the Office for Budget Responsibility published its latest appraisal of the UK’s fiscal risks and sustainability (FRS). It is a deeply disturbing document, highlighting three areas of concern: economic inactivity and health, energy-related risks, and debt sustainability. In the space of three years, the UK fiscal outlook has deteriorated beyond recognition. The irony is that the prime minister, the architect of extravagant and wasteful pandemic support programmes, also offers the best hope of a return to fiscal sanity. His likely replacement will arrive with new spending agendas. Rishi Sunak could resolve the impasse over public sector pay settlements by releasing resources within existing resource budgets by announcing an immediate unwinding of the recent expansion of the public sector payroll outside the sensitive departments of health and social care, education, and policing. This would have the added benefit of easing tensions in the labour market, releasing about 175,000 employees into alternative work.

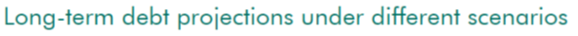

The loss of fiscal control (figure 1) is largely attributable to three distinct policy failures in the areas of energy security, pandemic response and monetary policy. The first is the longstanding failure to execute an energy security strategy, leaving the UK acutely vulnerable to the European energy crisis. The second failure occurred much more recently as the government embarked on a disproportionate and wasteful response to the pandemic. This was compounded by the Bank of England’s arrogant and bizarre decision to use its balance sheet to fund the government’s largesse in full, imparting an inflationary jolt and triggering a rapid normalisation of interest rates. This has rebounded on the public finances as a massive increase in debt interest cost, aggravated by the high proportion of inflation-linked debt.

A controversial but inescapable aspect of the pandemic response failure is the ongoing damage to the health of the general population, detailed in the OBR report. In its analysis of the surprising post-pandemic rise in economic inactivity, the report cites “the disruptive effects of the pandemic on people’s mental health and the treatment of non-Covid health conditions” and rising take-up of health-related benefits, which are typically more generous than other out-of-work benefits. As of early 2023, there were 2.6 million working-age people (6.1 per cent of the total) outside the labour force for health reasons. This may not capture fully the increasing numbers abstaining from work to care for a family member or friend.

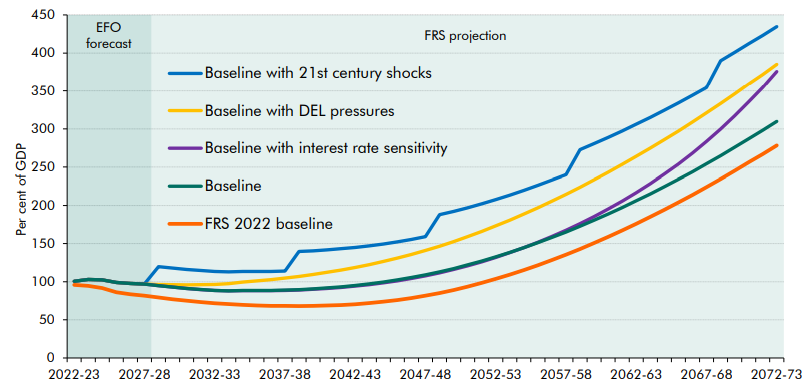

In the 4 years to 2023Q1, the public sector has added 8.6 per cent to its headcount (figure 2) and more than 10 per cent to its full-time equivalent workforce, a gain of 481,000. There has been a staggering 17 per cent increase in the FTE of the NHS, or 249,000. The nation desperately needs a resolution of the NHS pay disputes so that this enormous workforce can tackle the huge waiting lists and reverse the deterioration in health outcomes. This requires stringency elsewhere in the public finances, including staffing, grants and subsidies. There is a strong argument for the immediate unwinding of the 112,000 expansion in public administration FTE and the 59,000 gain in “other public sector” FTE over the past 4 years. According to the latest Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis (PESA), staff costs in 2021-22 were one-sixth higher than in 2019-20. Gross procurement costs were 38 per cent higher, current grants to persons were 11 per cent higher and subsidies to private sector companies were still running at £41bn, more than 3 times the pre-pandemic level.

It is time to call a halt to the public sector’s mission creep of the past 4 years: the costs are unaffordable, and the fiscal risks are escalating. The UK needs to send an urgent signal to domestic and international holders of its sovereign debt that the government is taking action to put its house in order. Public administration must shrink back to its former size and corporate subsidies must be heavily curtailed if the budget deficit is to be dragged down from the region of 6 per cent of GDP to its more sustainable 3 per cent of GDP.

Figure 1:

Note: This is for the headline measure of debt, i.e. including Bank of England.

Source: OBR

Figure 2:

Data source: ONS and EP calculations