Somewhere along the line, during the past 25 years, economic contractions acquired a stigma. Consecutive quarterly declines in GDP, alias recessions, became a national disgrace, a badge of shame. Any self-respecting government of an advanced economy would steer away from recession, not least to avoid handing political advantage to “the other side”. Our governing classes have created a mystical wonderland, Ainran, where it is always Christmas and never winter. As election year approaches in the UK, the desire to avoid a recession will surely intensify, but in truth, we need one. Waning momentum in private sector activity is tempting thoughts of prospective monetary easing, but bloated public expenditures are blocking the path.

Since the drama of Covid-19, and the temporary collapse of economic output and spending, the dominant macro narrative has concerned the recovery of pre-Covid levels of activity. Looking at Gross Domestic Product, the 2019 peak was exceeded for the first time in 2021 Q4 and the latest data (2023 Q3) places national output around 1.75 per cent above the strongest quarter in 2019. Even this modest uplift rests upon an adjustment to the accounts (described as a statistical discrepancy), without which GDP would be just 0.4 per cent proud of the 2019 peak.

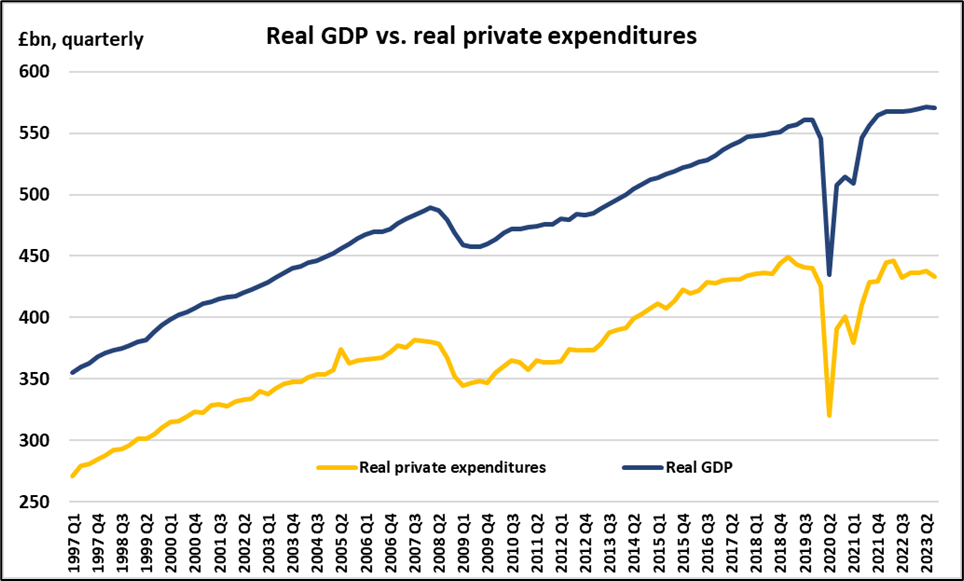

What is barely true for GDP, is most certainly not the case for the consolidated private sector – households, businesses and financial institutions. As figure 1 details, private domestic expenditures are languishing more than 3.5 per cent below their 2019 peaks. It has taken a sizeable expansion of public consumption and investment spending, plus a little help from a narrowing overall trade deficit and the insertion of a statistical adjustment to hoist GDP above the 2019 record. Acknowledging that the UK population has increased by around 1.5 per cent over the past 4 years, there is scant improvement in GDP per capita.

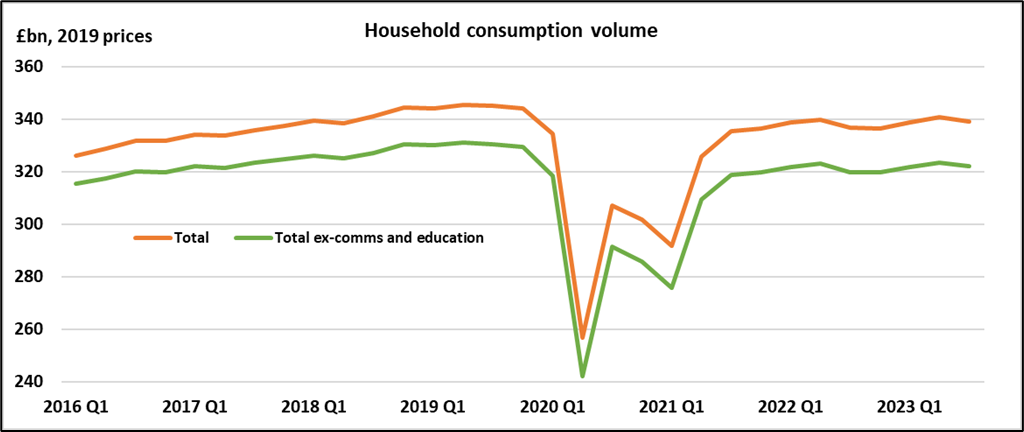

Similarly, household consumption languishes 1.8 per cent below its high-water mark in 2019. An examination of the sectoral data reveals that only 4 out of 12 headings recorded a real gain in spending since 2019: communication (+26.9 per cent), education (+15.6 per cent), restaurants and hotels (+8.3 per cent) and housing and domestic utilities (+2.7 per cent). The list of negative comparisons stretches from health (-2.1 per cent) and food and non-alcoholic beverages (-2.2 per cent) to clothing and footwear (-6.3 per cent) and transport (-15.4 per cent). Retail sales data provides a more detailed commentary, including grim data for October: sales volumes (excluding automotive fuel) were weaker than in October 2018.

The harsh reality is that the post-Covid private sector output recovery stalled about a year ago. Service industries as a whole (79.4 per cent by weight) are stagnating, with only arts, entertainment and recreation sporting strong quarterly growth. Is it conceivable that the UK could squeeze out another year of statistical growth in 2024? Just about. But this would only leave 2025 doubly exposed to a contraction. The government has pulled out all the stops to cultivate the appearance of a sustained, if shallow, recovery. Bloated public expenditures and staffing levels are blocking the way to the easing of monetary policy that the private sector craves. Economic winters should be accepted as a healthy precursor to economic springs. Higher interest rates and tighter credit access must be allowed to do their work, even in election years.

Figure 1:

NB: Private expenditure is defined as private gross final expenditure minus acquisitions less disposals of valuables

Figure 2:

Data source: ONS