In a recent speech Huw Pill, the chief economist of the Bank of England, repeats the assertion that wayward UK inflation is largely the outcome of external shocks, factors outside the control of the monetary authorities. Nothing could be further from the truth. The unwillingness of central bankers – in the UK and elsewhere – to acknowledge the responsibility they bear for the resurgence of inflation is a huge obstacle to the formulation of sensible policies today. Belated enthusiasm for interest rate hikes and asset sales could have disastrous effects on financial stability and for the real economy. Lenders are tightening credit conditions in their own interests and the financial sector’s access to cheap credit is evaporating. The likely abatement of inflation next year heralds the mutation of the crisis, not its end.

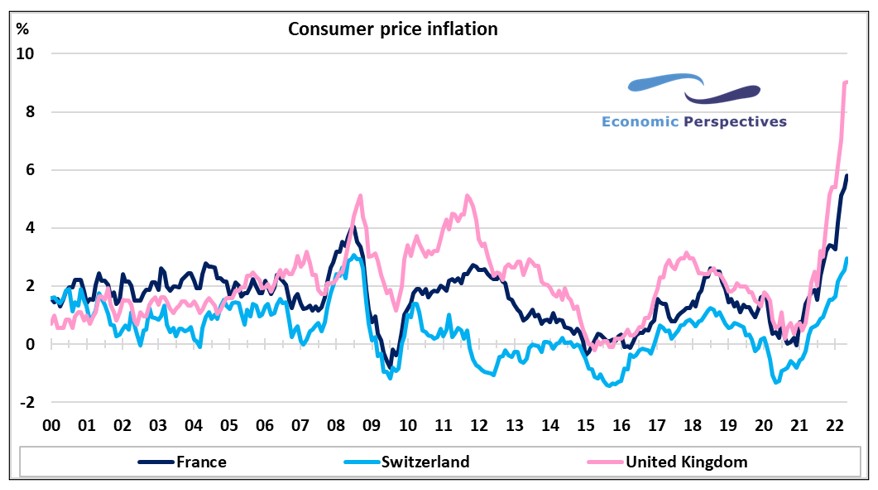

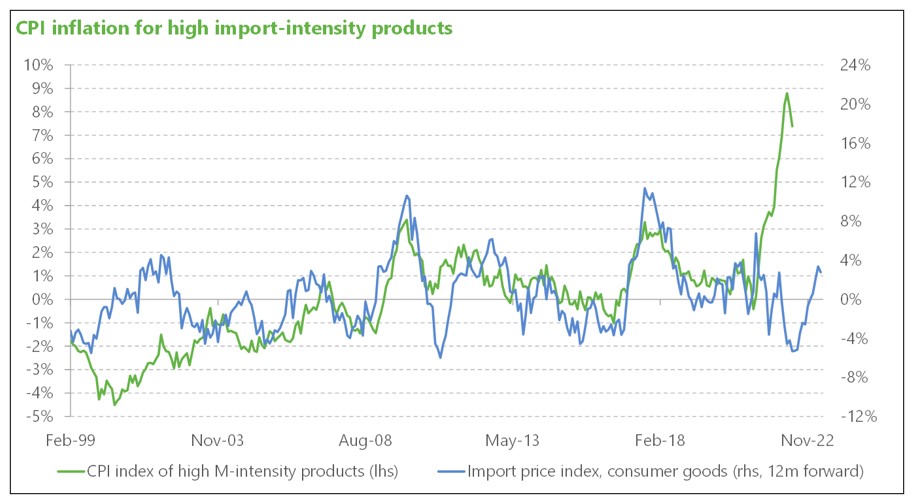

“In large part, recent price developments have been driven by a succession of unanticipated external disturbances to the UK economy – among others, the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.” Thus, Huw Pill summarises the UK’s ‘bad luck’ with inflation. There are numerous problems with this characterisation of events, but let’s concentrate on two. First, some developed countries, such as France and Switzerland, have seen much more muted increases in inflation (figure 1) despite their exposure to the same “adverse external shocks”. Second, UK import inflation, as measured by the relevant deflator, remains quite low (figure 2). This suggests that it is the retail margins on scarce imported items that have expanded, rather than the prices of the items.

The primary role of Covid-19 in our inflationary woes was to trigger policy madness: a combination of multiple and extended economic lockdowns, over-generous subsidies, government-guaranteed bank loans and the bizarre decisions of the Monetary Policy Committee to monetise the excess budget deficit in full. These policies created the purchasing power that fuelled a consumer goods boom and a bonanza for corporate sector profitability in certain sectors. These errors were compounded by a significant expansion of public sector employment – at least 500,000 – which exacerbated labour shortages in the context of a mass withdrawal from the labour market in the older age groups.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine aggravated the European energy supply crisis that had begun months before. Successive UK government policies have compromised energy security through the demonisation of fossil fuel investment, a lack of gas storage facilities, the imposition of ‘green’ taxes and duties and an ambivalence over the expansion of nuclear energy capacity. The expression of inflation in high fuel and heating bills derives from a lack of resilience in energy infrastructure. France and Switzerland, with much better infrastructures, have averted such an extreme outcome. Germany’s predicament is even worse than ours.

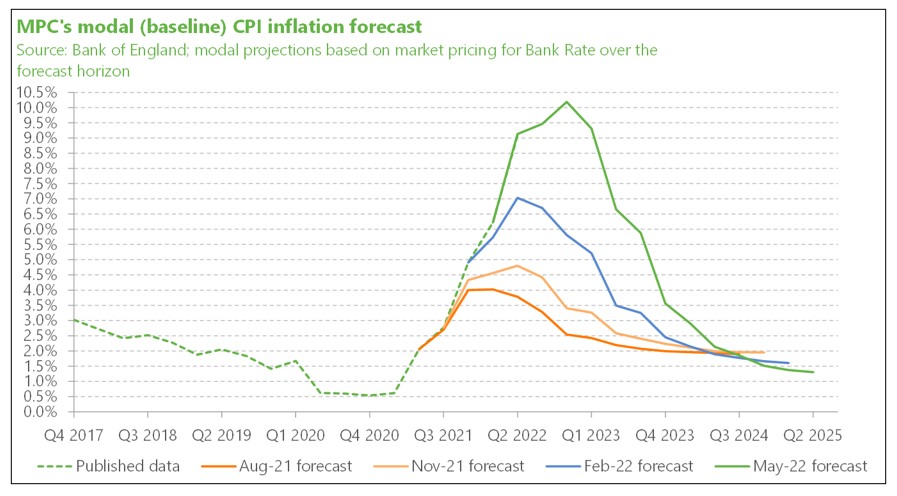

The Bank of England’s dismayed (figure 3) reaction to the prospect of 11 per cent inflation in October-November is to consider larger interest rate hikes and the shrinkage of its balance sheet. But the damage is done. Consumers are hunkering down for a tough 12-18 months. Businesses will soon feel the pinch as the inventories they have worked so hard to rebuild, will prove excessive and unwanted. The Bank is stumbling towards overkill as it seeks to demonstrate its earnestness in defeating inflation. Rather, it should be monitoring financial stability risks as market liquidity vanishes. And expect the government soon to be rushing to the aid of the economy with a significant fiscal relaxation.

Figure 1:

Data Source: Macrobond

Figure 2:

Data Source: Jamie Dannhauser, Ruffer LLP

Figure 3:

Data Source: Bank of England

Weeell, yes, but… It can certainly be argued that external shocks (especially the big one of surging energy due to Putin’s Petulance) are not to blame for inflation in the UK. It then however becomes hard to argue that the French have sidestepped the problem because they have a better energy situation – presumably referring to their enviable abundance of nuclear power. Is it energy or is it not…?