Like a pillion passenger leaning in the opposite direction to the rider, UK banks’ behaviour has become perverse and dangerous. Banks are engaged in an elaborate risk management exercise that seeks to defend their profitability and reputation and conserve their capital. Their role as credit intermediaries to individuals and non-financial businesses is being increasingly subordinated to these other considerations. Their willingness to withdraw from the marketplace – in terms of physical footprint, product range and customer profile – is symptomatic of their reordered priorities. Policymakers can no longer have any confidence that a cut in short-term interest rates will have an expansionary effect on bank lending to the real economy, nor that a hike in interest rates will necessarily have a restraining impact. However, the stimulus imparted from large scale central bank asset purchases to lending to the non-bank financial sector – on the expectation of rising financial asset prices – has reversed since the adoption of quantitative tightening. The squeeze is on.

When the financial crisis erupted in 2007-08, the nature of commercial banking would soon be transformed by regulatory interventions. Alongside the traditional role of credit intermediation, banks were forced to become professional risk managers. Liquidity and solvency risks that they had previously assumed to be covered by the central bank, landed back in their lap. In consequence, banks became much more cautious in their lending to the real economy. Year after year, loan growth languished despite very low interest rates. Like a car whose driver has one foot pressed down on the accelerator and the other pressed down on the brake, the wheels of the economy were spinning but the vehicle was stationary. Post-GFC, governments in advanced economies sent an expansionary message with historically low interest rates while simultaneously sending a contractionary message with its regulatory impositions.

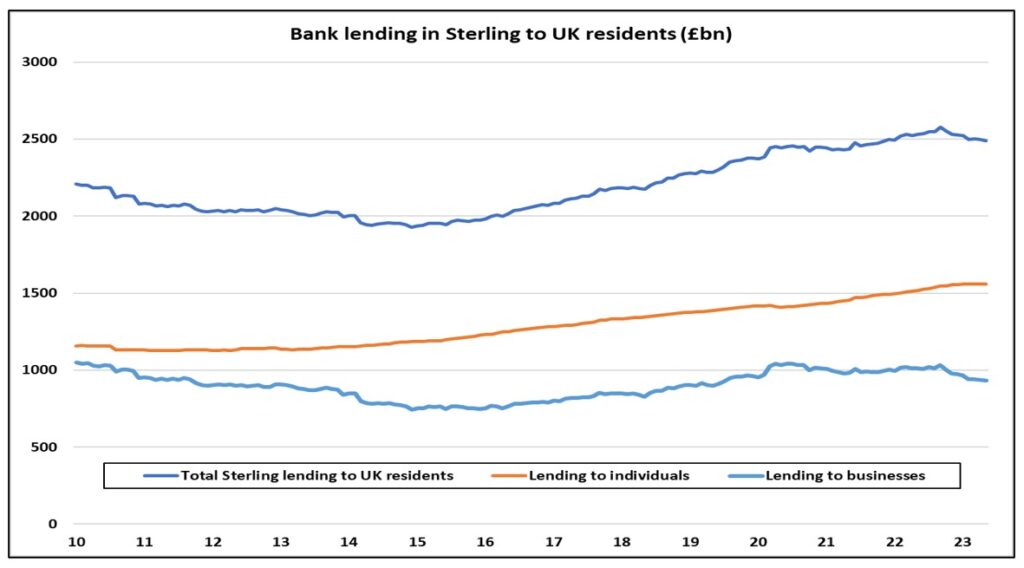

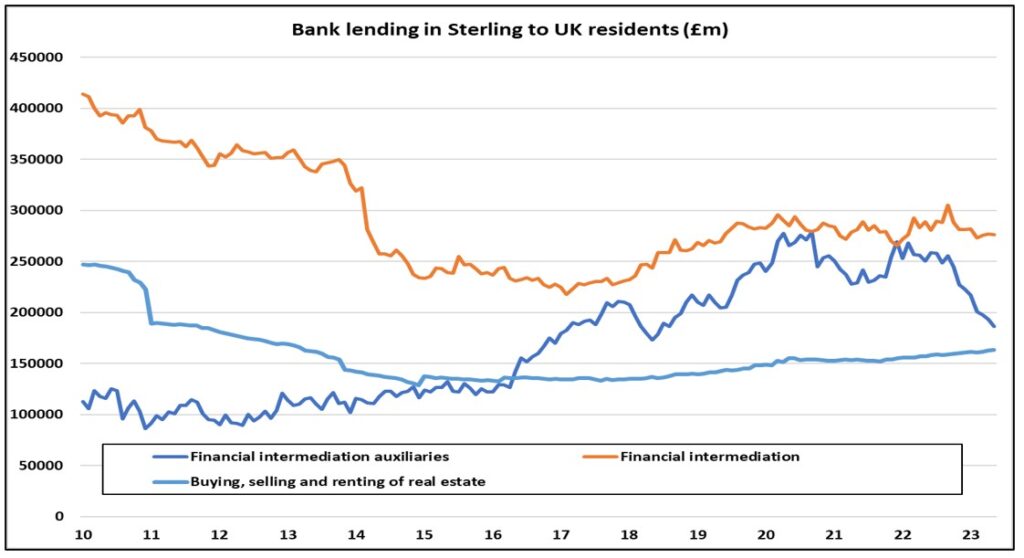

In 2023, UK banks are at it again! They are reinforcing the impact of rising policy interest rates with a severe tightening of lending conditions for the non-bank financials who are the marginal providers of credit to real economy borrowers – confiscating the umbrellas before the real downpour arrives. Figure 1 illustrates the effort that banks are making to restrict net lending to individuals and to contract net lending to businesses, especially financial businesses. Figure 2 reveals that it is the financial auxiliaries (mainly fund managers) whose borrowing has been most severely curtailed. (One might ask why they needed to borrow so much in the first place?)

Commercial banks are on a mission to extract themselves from their traditional exposures to consumers and small businesses. A rich variety of shadow banks has emerged – insurance companies, credit providers, leasing companies etc – to engage with retail customers. Since the GFC, the banks have prioritised funding of other financial intermediaries above lending directly to individuals and small and medium-sized enterprises. This has two advantages for the banks: it distances them from the painful human consequences of rising rates, and it offers them a better risk-adjusted return. In a recession, the banks will still take a hit on their loan book, but more from lending to failing non-bank financials, and less from lending to John Smith and Miriam’s nail bar.

Rather than offering their depositors a decent rate of interest as a buffer against the adverse impacts of inflation, they are withholding return in a bid to protect their capital from prospective loan losses. In desperation, the government is attempting to shame the banks into concessions, seeking to recompense savers and soften the blow of resetting mortgages and avert the spectacle of a pre-election wave of house possessions. The banks will argue that they are taking justifiable steps to protect their capital, but from a societal perspective, banks have become rogue actors to the frustration of consumers, SMEs, and government alike.

Figure 1:

Data source: Bank of England, Bankstats

Figure 2:

Data source: Bank of England, Bankstats