A feature of the past 18 months has been the extraordinary level of vacancies, or job openings, throughout the developed world. While the pandemic triggered an expansion of public sector employment, especially in English-speaking countries, the post-Covid reopening of service sector businesses overlaid an urgent requirement for personnel in retailing, leisure and hospitality. Employers have been falling over themselves to fill vacancies with qualified and competent staff, offering joining and loyalty bonuses in some cases. In the US, this phase of frenzied matchmaking has given way to anxious concern for the state of the economy next year; similar dynamics are starting to unfold in the UK and in a few Euro area countries. Can vacancies fall sharply without a commensurate rise in unemployment?

A detailed analysis of UK vacancies reveals a 7-fold increase for accommodation and food service activities relative to 2 years ago. Threefold and fourfold increases are typical. What we must decide is the extent to which this escalation in vacancies – about 3.7m in the US and 800,000 in the case of the UK – reflects the withdrawal of similar numbers from the workforce since summer 2020. The appearance of a vacancy does not presume that there is anyone available and willing to fill it. Hundreds of thousands of positions have remained unfilled for long periods of time, suggesting either that there is a physical dearth of qualified applicants or that these jobs are unattractive, for reason of poor pay or lack of tenure, or both.

It is conceivable that many of these vacancies reflect merely the aspirations of employers to hire more staff. For such positions to remain unfilled may not present a constraint on the current activities of the employer, who equally has no incentive to make the vacancy more appealing to jobseekers. Conversely, some employers may be desperate to fill a vacancy – because the viability and integrity of their activity depends on it – but are unable to improve the terms and conditions because of budgetary constraints.

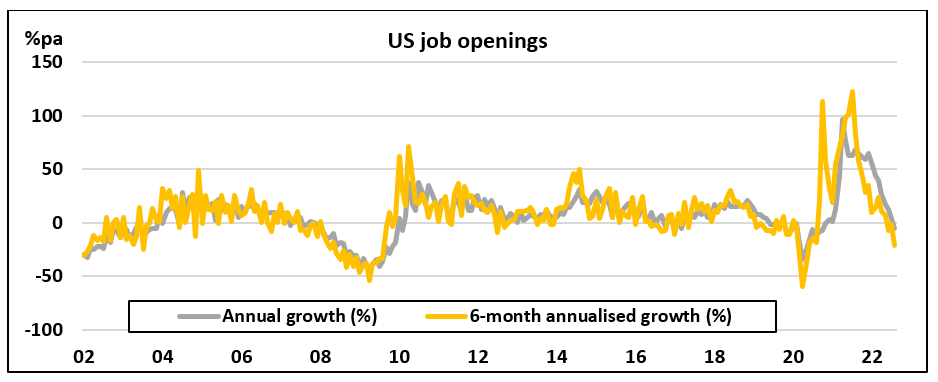

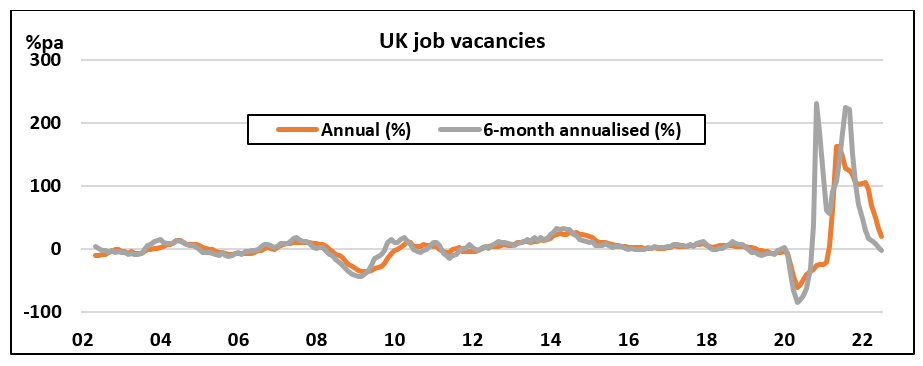

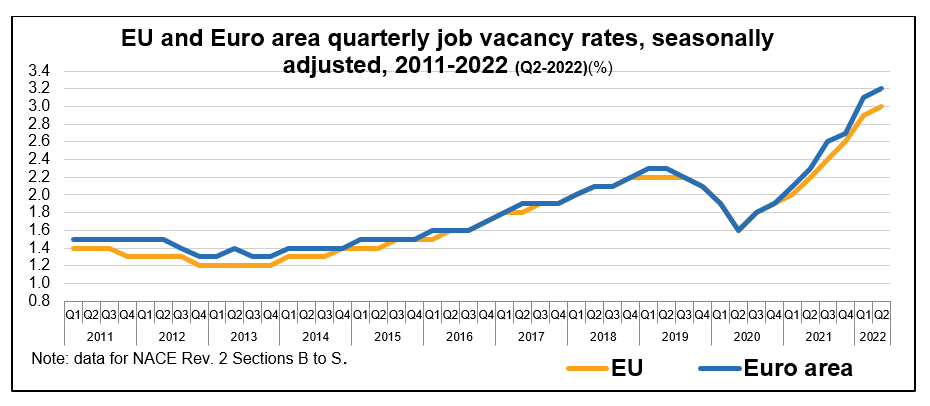

What is clear from figures 1 and 2, is that the stock of job openings has negative momentum: in the US, the 6-month annualised rate of change is -22.5 per cent. Around 1.8m positions have been filled or have been withdrawn since March. In the UK, the drop in vacancies has been concentrated in businesses employing less than 50 employees – a 16 per cent annualised fall in the past 6 months. The EU countries are harder to judge, but vacancies in southern and eastern European countries look to be ebbing. Prepare for a bonfire of the vacancies over the next 12-18 months, but in the context more of their withdrawal than their fulfilment. Unemployment rates are set to rise in US, UK and EU, but by much less than the collapse of vacancies might suggest.

Figure 1:

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Figure 2:

Source: Office for National Statistics

Figure 3:

Source: Eurostat (online data code: jvs_q_nace2)